What if you could own 10, 20, or even 50 acres of European land for less than a small apartment in a big city (and you could actually live well there)?

Sounds absurd?

Many people believe that farmland in Europe is now too expensive.

But that’s not true.

You can still buy European farmland for around €1000 per acre.

I’ve spent the last 5 years helping people in Europe, and found 15 regions where land is still affordable, the soil is good, and the rules for non-European buyers are simple.

Yes, even today you can still buy great farmland in Europe without being rich or having an EU passport.

The higher we go in the ranking, the more the numbers line up in your favor. Stay to the end, because the top three regions combine low prices, fertile land, and one of the easiest buying processes in Europe.

Yet, most people never hear about them.

The Criteria To Define the Best Cheap Places to Buy Land in Europe

I used four factors to build this list of cheap places to buy farmland in Europe.

- First, purchase legality for you as a non‑EU buyer. If you cannot own or control farmland in a straightforward way, that country is out. Hungary or Poland, for example, on paper allow non-EU citizens to own farms, but they require special permits from the government that are extremely difficult to obtain. So we didn’t include these countries in our list.

- Second, price per hectare. Remember that one hectare is the same as 2.5 acres, so to have the price per acre, just divide the value we will give you by 2.5.

- Third, water and legal water rights. We favor regions where you can either access irrigation or at least verify a registered well or license.

- Fourth, practical livability. We use a “Rule of 50 minutes” to a major hospital, plus basic internet and services. Farming involves chainsaws, tractors, and accidents, so you want a hospital not that far.

On top of that, we add hidden costs: clearing scrub, fencing, drilling and legalizing a well. That’s why some mid‑priced regions score higher than the absolute cheapest. Now that you know the rules of the game, let’s start the ranking with…

Number 15: The Budget Workhorse

Our first stop is Extremadura, in Spain.

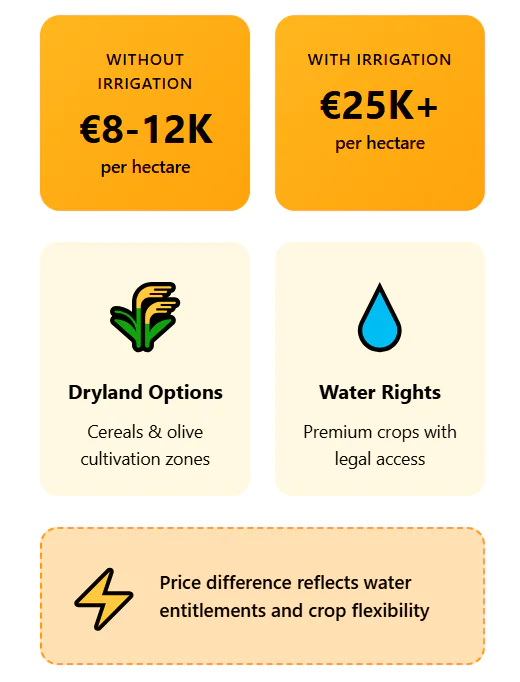

The provincial capital, Badajoz, has around 150,000 residents, which gives you hospitals, services, and a labor pool, while you still farm in a very rural context a short drive away. The key point here is the two‑tier land market. Dryland farms usually change hands around €8,000 to €12,000 per hectare.

Once you add irrigation, the price jumps above €25,000 per hectare. That gap exists because irrigated land carries water rights and can host higher‑value crops, but even dryland can be useful for certain crops, like olive groves. Badajoz produces industrial tomatoes at scale, and stone fruits like peaches, nectarines, and plums at irrigated fields.

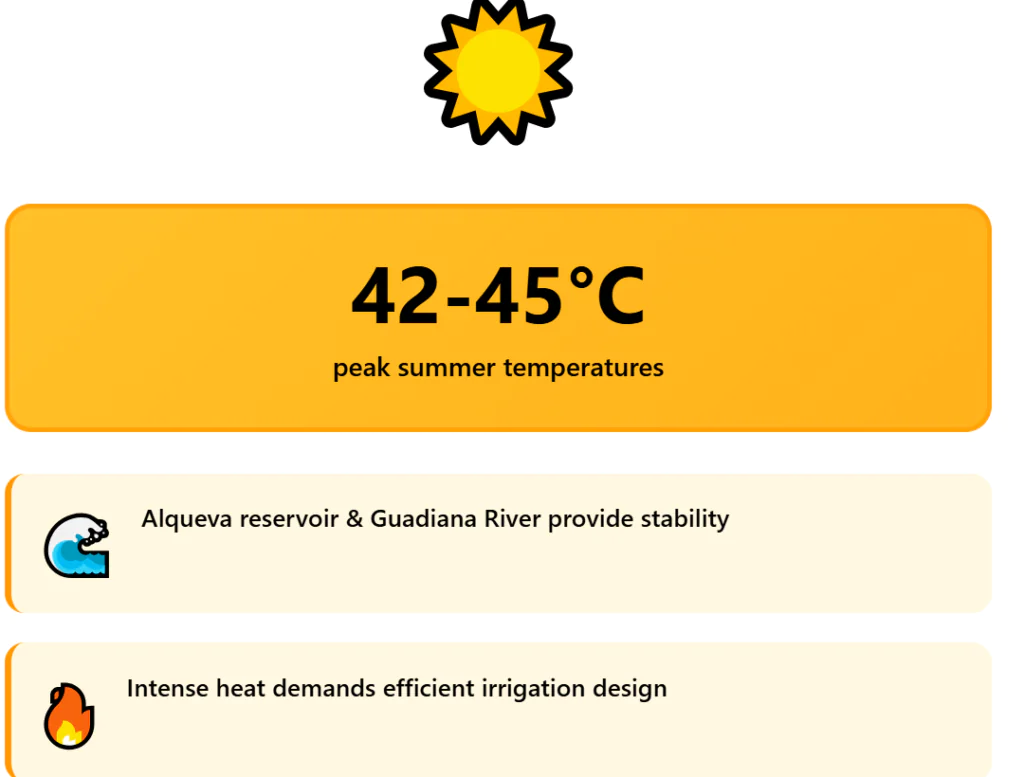

Meanwhile, cheaper non-irrigated fields can be used for dry cereal ground and basic olives groves. The Alqueva dam in Portugal and the Guadiana River give this area a more stable water picture than other parts of Southern Spain, but the right to use that water has a price.

Summer heat is a real constraint. Temperatures often reach 42 to 45 degrees Celsius. That means water losses, crop stress, and higher energy use for irrigation.

If you plan anything beyond resistant cereals, olives, or very heat‑tolerant crops, you need efficient systems from day one. For non‑EU buyers, the legal path is direct. You obtain an NIE, open or use a Spanish bank for the transfer or bank check, and complete at the notary.

Combine that with highway links straight to Madrid and Lisbon, and Badajoz becomes a proper choice for cost‑controlled projects, if you respect heat and water as hard limits. But if you want cheaper land prices and some of the best soils in Europe, the next place is for you.

Number 14: The Fertile ‘Wild East’

North‑East Romania, the historical region of Moldova, is where you trade comfort for raw agricultural potential.

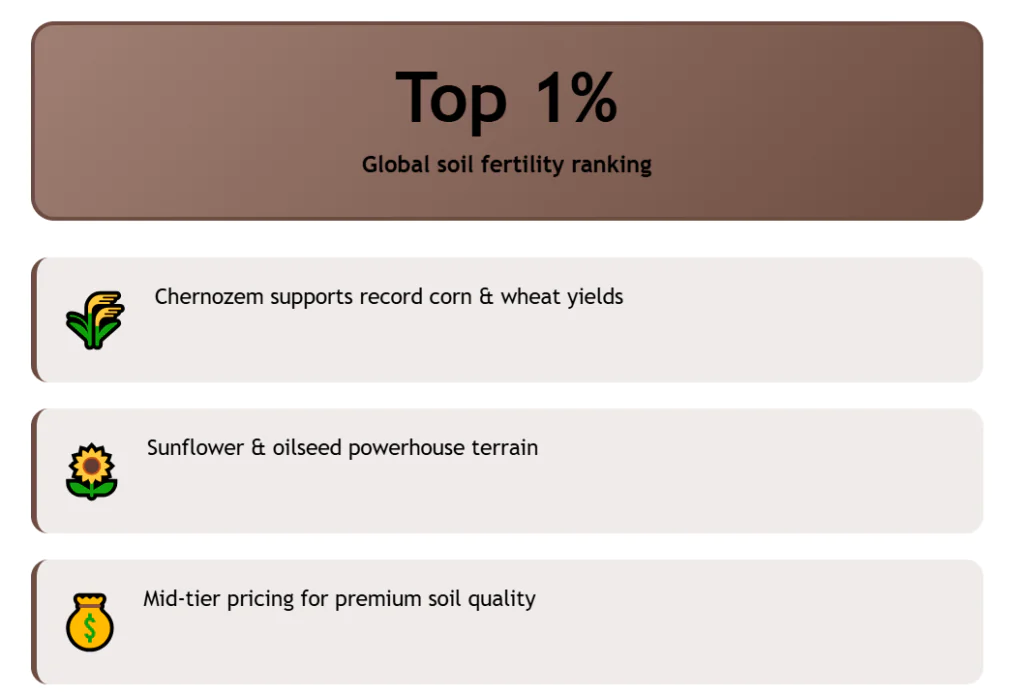

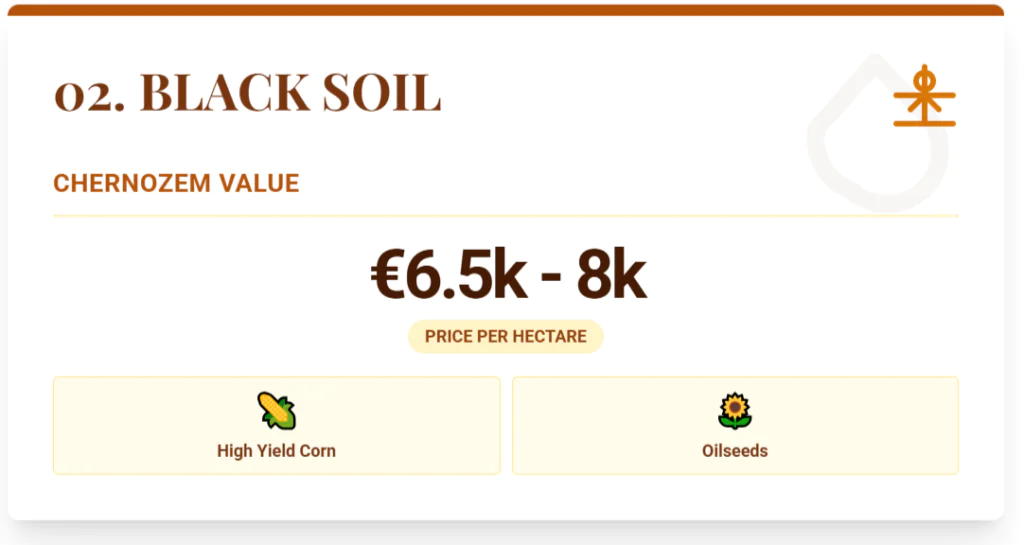

The main urban center of this region is Iași, with a population close to 300,000, a regional airport, and higher‑level hospitals. Farmland prices in this region usually range from €6,500 to €8,000 per hectare. That puts Moldavia below Western Romania and well below Western Europe, even though you get Chernozem soils, which rank among the most productive globally.

Those black soils support high yields of corn, wheat, and sunflowers, plus other oilseeds and industrial crops. Romania receives substantial CAP funds, and if you own a local company, you can apply for EU grants that finance tractors, storage, and irrigation upgrades. Non-EU buyers need to establish a local company (a Romanian SRL); it is not a huge expense, but you must factor it into your costs.

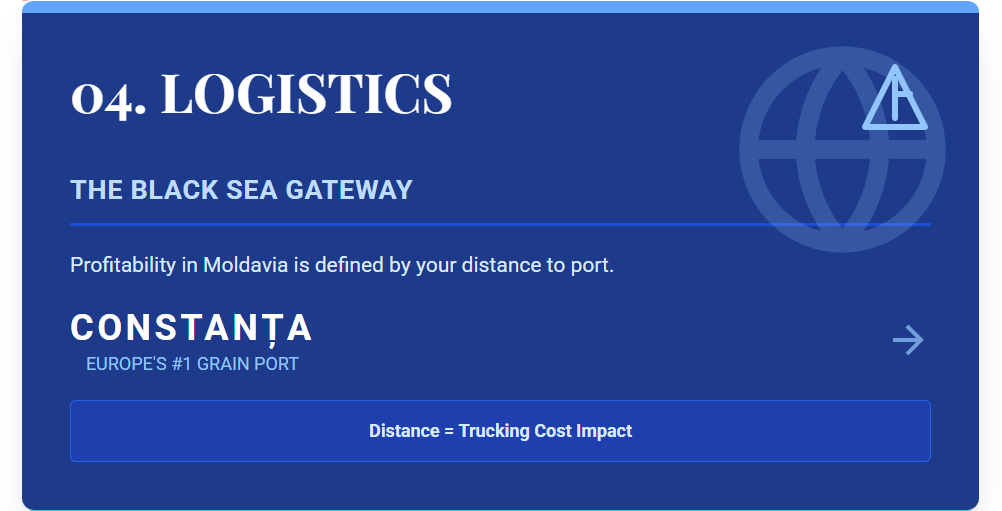

Infrastructure adds another layer. Road and rail networks there lag behind Spain or France, so moving grain to the port of Constanța takes more time and more fuel. On top of that, North‑East Romania lies close to Ukraine, which brings geopolitical risk and investor nerves.

You also face a slow pre‑emption process: Every sale passes through a 4–6 month window where neighbors and the state can exercise priority. Combine that with fragmented plots and possible title gaps, and you need strong legal support and patience to build scale. From the Wild East environment, we go back toward the center of Europe.

Number 13: Big Flat Fields Two Hours from Paris

If you want a French farm without Paris prices, Indre is where we start looking.

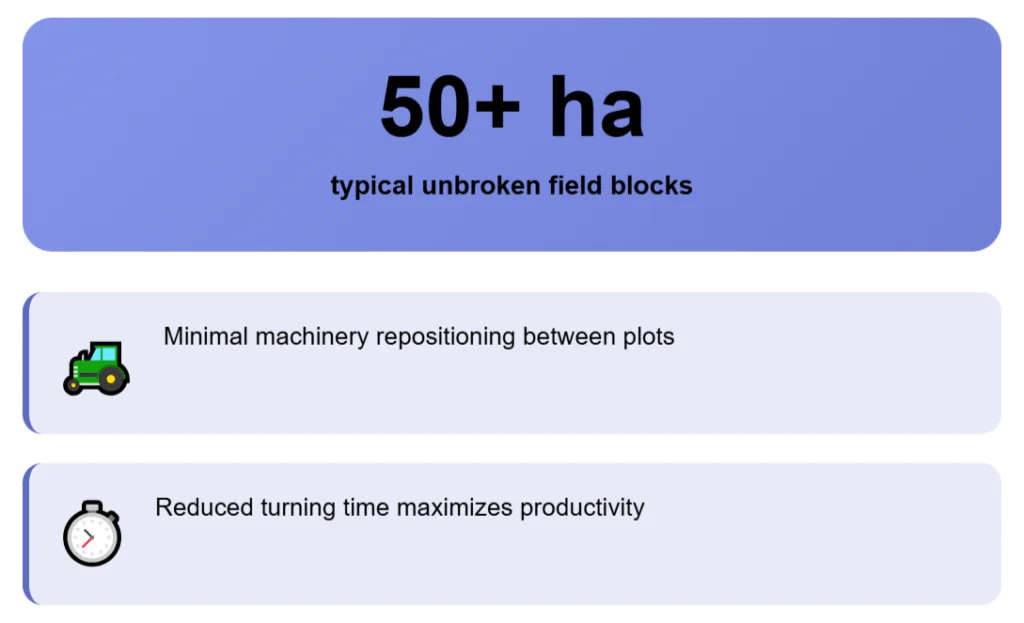

We are in Centre‑Val de Loire, on the Champagne Berrichonne plateau, a landscape built for scale. What makes Indre stand out is block size. You regularly see plots over 50 hectares in a single piece.

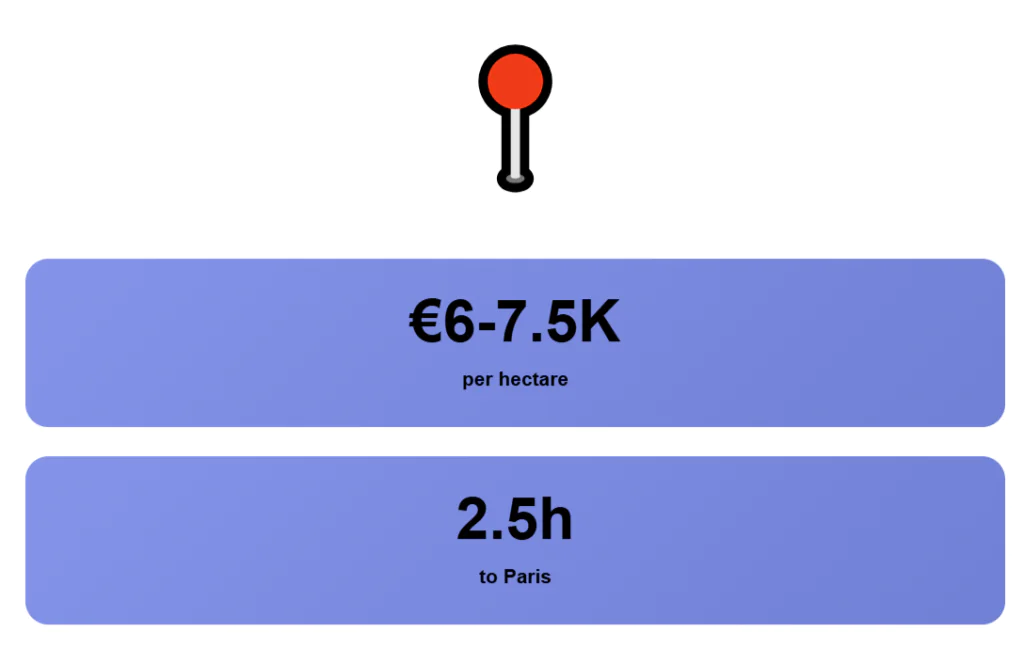

That matters because one tractor fleet and one worker can cover more ground with less wasted time turning around, moving machinery, or dealing with hedges and boundaries. Land there usually trades around €6,000 to €7,500 per hectare. It is not the lowest number in Europe, but you get central positioning.

You are about 2.5 hours south of Paris by road, with direct access to the Rungis wholesale market, which is one of Europe’s key food hubs. Large cereal fields dominate, with wheat, barley, and rapeseed as the main crops. On top of that, you have goat dairy supplying cheeses like Valençay and Pouligny‑Saint‑Pierre, so you can combine grains with higher‑margin premium milk.

But there are constraints too. Aquifers here face pressure, and summer water restrictions can cut irrigation when levels drop. The Agency SAFER can also pre‑empt a sale and redirect land to an established farmer or a young local, which means you need a clear project and good advice before you sign anything.

Think of SAFER as an over-attached mother-in-law: she has an opinion on everything you do, and she can cancel your plans at the last minute.

But if you’re feeling overwhelmed by the European bureaucracy, on my Patreon, I answer questions directly and share the specific contacts and sources that clarify this mess. Tier 1 is just $5 a month – the price of a coffee, and for that you’ll also get my best-selling Ebook, over $108 worth of updated reports, and access to the sources i use. Join us there, and discover what Europe can offer to you.

Number 12: Authentic South

Between Tuscany and Puglia, Basilicata gives you a much less hyped, and also cheaper scenario.

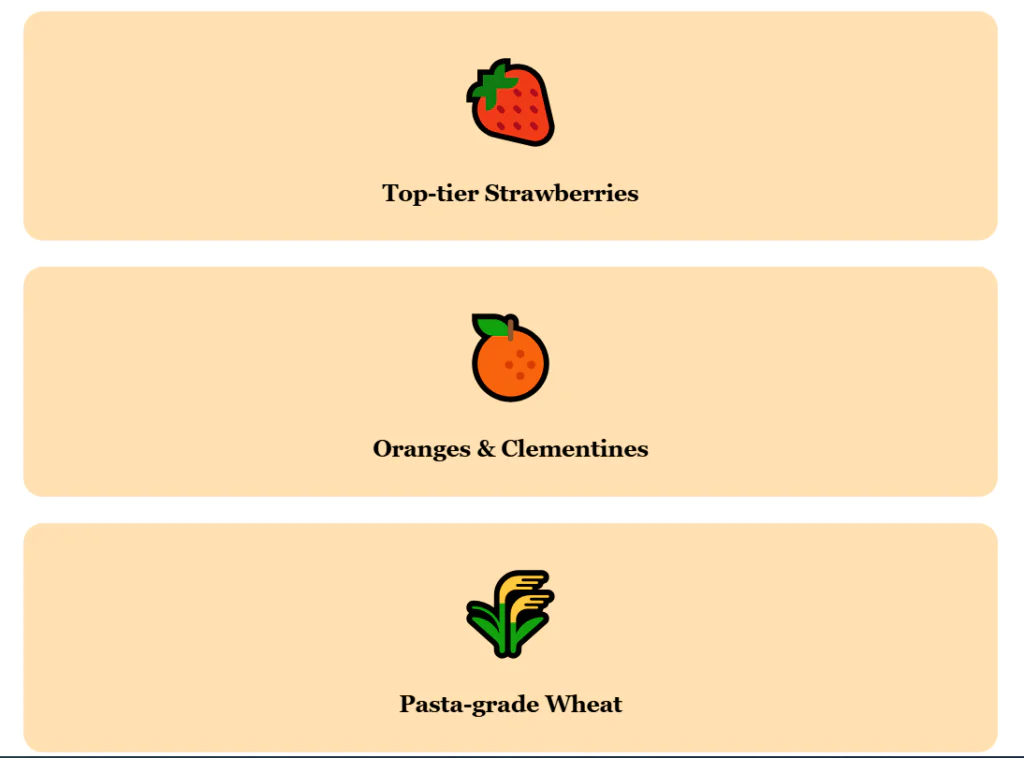

On the coastal strip near Metaponto, farms focus on strawberries and citrus. The Metaponto area is known for strawberries that rank among the best in Italy, plus oranges and clementines in the same coastal belt. Inland, the hills move into durum wheat.

That crop underpins pasta production and anchors the interior farm economy. Smaller, specialized farms are common, because the terrain does not favor massive, flat blocks. Farmland prices range from €11,000 to €16,000 per hectare, which means around US$4,900 to US$7,000 per acre. A price similar to Kentucky or Tennessee in the US.

That places Basilicata well below Italy’s average price per hectare of farmland. Near the coast, where strawberries and citrus generate higher turnover per hectare, that price band looks competitive if you manage water and labor.

Water is the first hard filter there. Interior areas face drought risk. Without a registered well or formal irrigation rights, your land value and cropping options drop fast. You want clear documentation of water rights before you even think about a deposit. Otherwise, you hold an asset that you cannot farm intensively. Terrain adds cost.

Hilly blocks make mechanization harder, raise fuel use, and slow every field operation. For non‑EU buyers, Italy uses the reciprocity rule. If people from your country can buy land in Italy, you can buy Italian land.

One advantage over France is that in Italy there is no SAFER‑type body. You work with a notary, handle detailed paperwork, and then you can plug into agritourism demand around Matera with farm stays and niche products.

Number 11: Polyculture, Oak Forests, and Sticky Clay

Allier in Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes is a classic mixed-farming department.

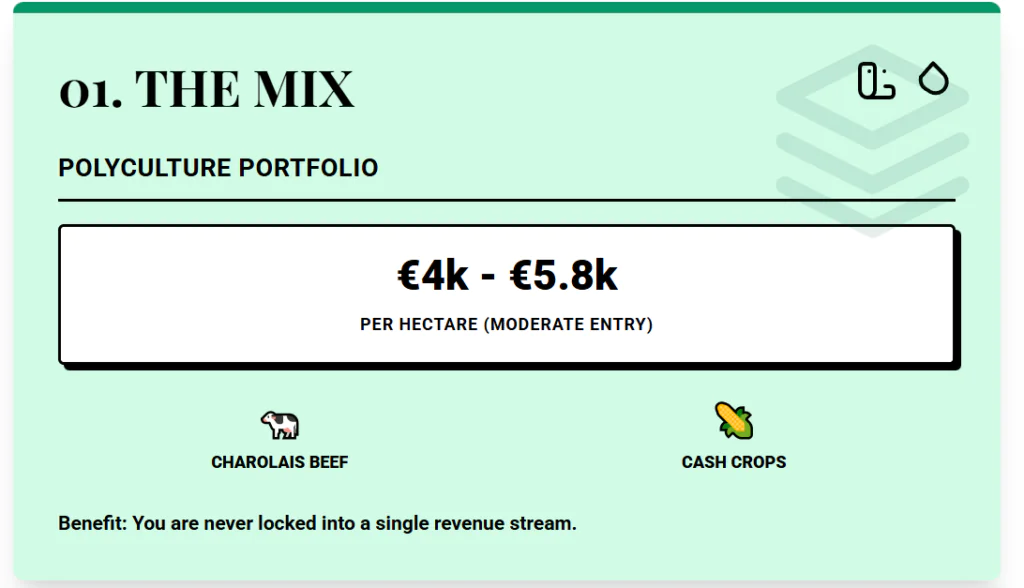

One of the main urban centers is Vichy, with about 25,000 residents, known for its spa economy and for something that happened there between 1940 and 1944. From the flat grain land in the north to the early slopes of the Massif Central in the south, you get a transition from open fields to more wooded, livestock-friendly areas. Farmland prices usually range from €4,000 to €5,800 per hectare.

For Western Europe, that band is moderate when you factor in the range of uses: Charolais beef herds, Label Rouge poultry, maize, soy, and sunflowers, plus oak forests that supply wood for barrel-making. That mix means you are not locked into a single crop model; you can run cattle on pasture, grow feed, and keep some hectares in cash crops. The main technical constraint is the soil.

Bourbonnais clay holds water in summer but creates drainage and access issues in wet periods. In a rainy spring, heavy clay can delay field work, which affects planting windows and yields for arable crops.

On the institutional side, the SAFER agency plays a strong gatekeeping role.

It tends to favor professional or well-structured projects and can pre-empt a transaction. Gentleman Farmer estates, often with a 19th‑century house and decent acreage, absorb part of the supply and can push prices on the most “ready-made” farms. Life in Allier is calm, with access to services but less hype than wine-famous areas, which can slow resale for atypical properties.

It fits best if you want mixed farming—cattle, forestry (Allier is famous for the Tronçais Oak), and some crops—and are ready to work within SAFER’s rules and limits.

Number 10: Under-the-Radar Truffle and Olive Country

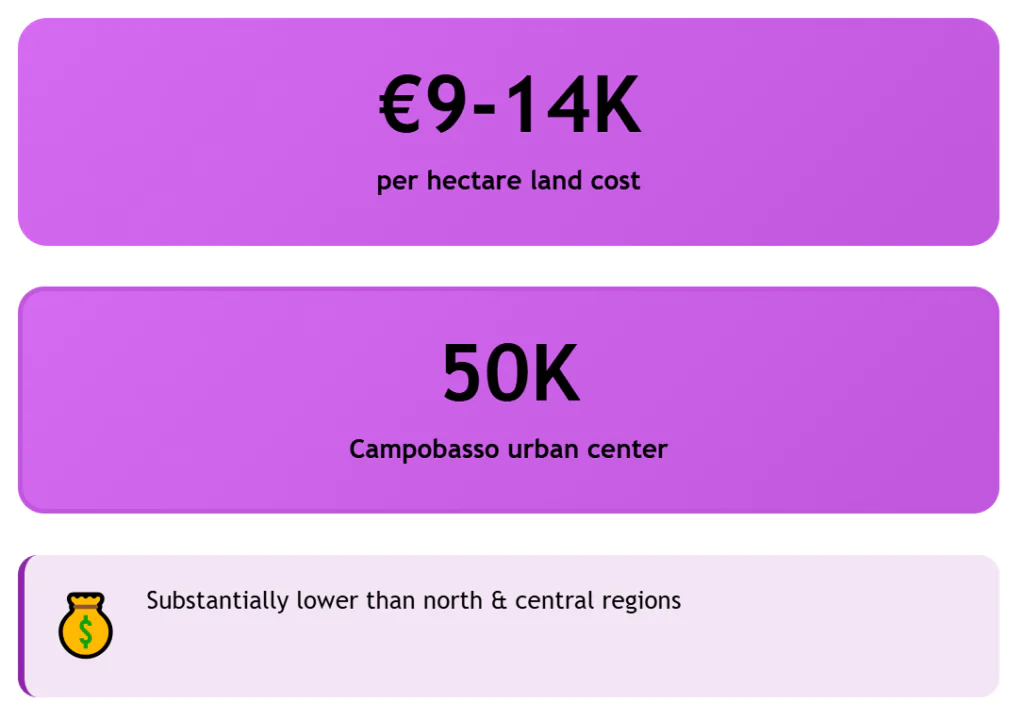

Molise is one of the few Italian regions where you still get farmland at a discount.

The main urban center is Campobasso, with around 50,000 people. Land prices there usually range from €9,000 to €14,000 per hectare, well below many parts of central and northern Italy. Old olive groves produce high‑quality oil.

Vineyards with the native Tintilia grape give you a regional wine with a clear identity. On top of that, Molise accounts for about 40% of Italy’s white truffle production. So you have three high‑value products—olive oil, wine, and truffles—on the same map.

Daily life in Molise leans on small villages, low crime, and long‑standing traditions. That mix makes agritourism viable: farm stays, truffle hunts, olive harvest weekends. Now the trade‑offs.

Depopulation reduces the local workforce. That can make harvest labor for olives or grapes more expensive or harder to find. The hilly terrain limits very large, fully mechanized operations and increases fuel, machinery wear, and labor per hectare.

Infrastructure is another filter. You drive longer to reach major airports and big hospitals in Bari or Naples, and road networks are weaker than in the north. For non‑EU buyers, Italy’s reciprocity rule applies: if your country lets Italians buy land, you can usually buy in Molise, with less competition than in regions like Tuscany.

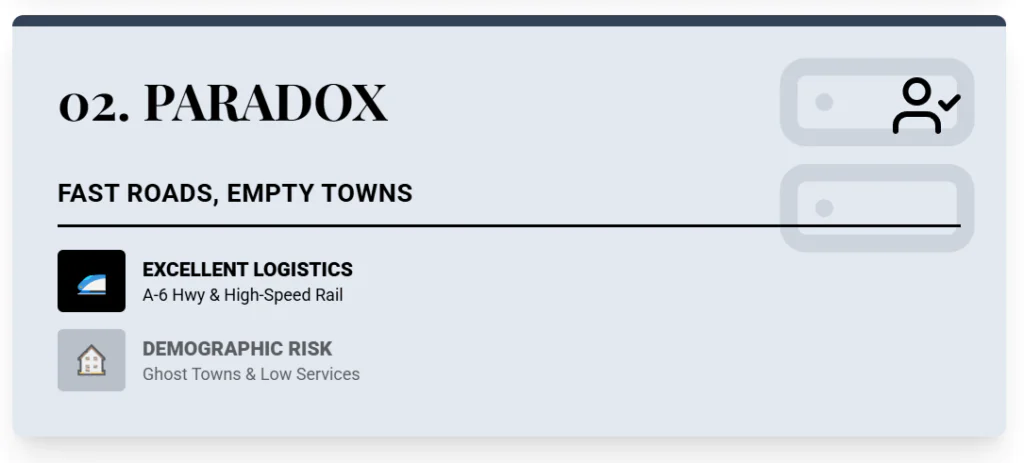

Number 9: Traditional Castilian Fields with Modern Road Links

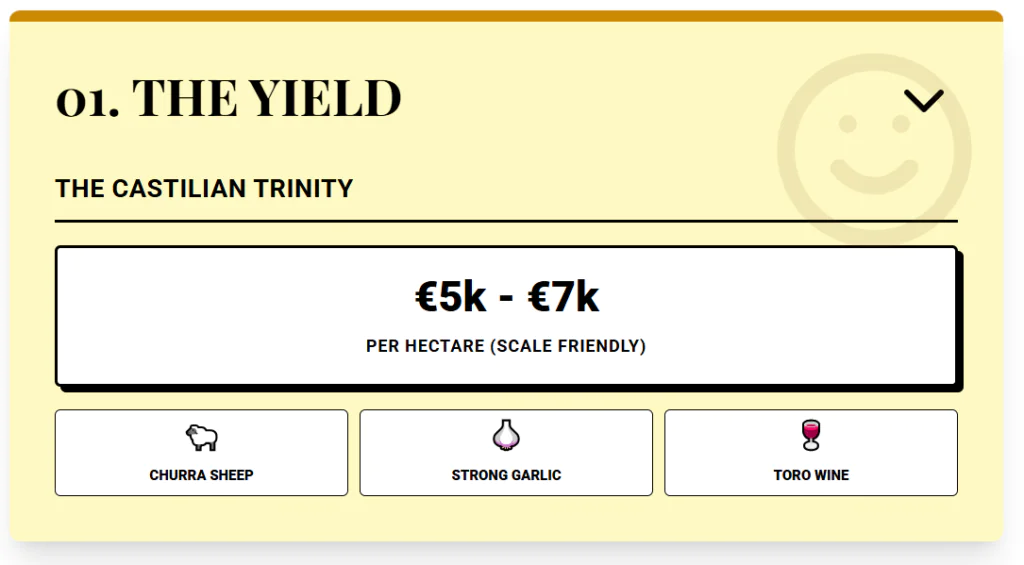

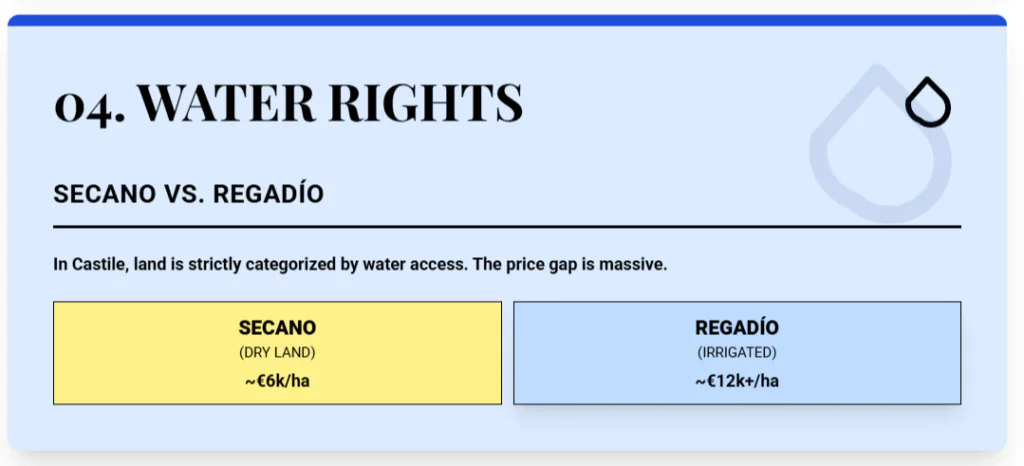

We are talking about Zamora, in Spain, where farmland usually ranges from €5,000 to €7,000 per hectare.

At that level, you can buy meaningful scale without going into city‑level budgets. Zamora has deep agricultural roots: Churra sheep for meat, wool, and milk used in local cheeses, strong garlic production and direct influence from the Toro wine area, known for powerful red wines. Inside the denomination, vineyard land costs more, but just outside you still find fields at the lower band.

The A‑66 highway give fast links toward Sevilla and Galicia, and road corridors connect you toward Portugal. If you need to move lambs, garlic, or wine to wholesalers, those links cut travel time and fuel costs. But you must weigh that against demographics.

Many villages lose people and turn into near “ghost towns,” reducing local services. You will have a long drive for basics if you pick the wrong hamlet. Also, high density of wolves in the Sierra de la Culebra area pushes sheep farmers to spend on fencing, guard dogs, or secure night barns.

For non‑EU buyers, Spain’s process is clear: get an NIE, use a Spanish bank, and close at the notary. Remember to check if the property is dry land or irrigated.

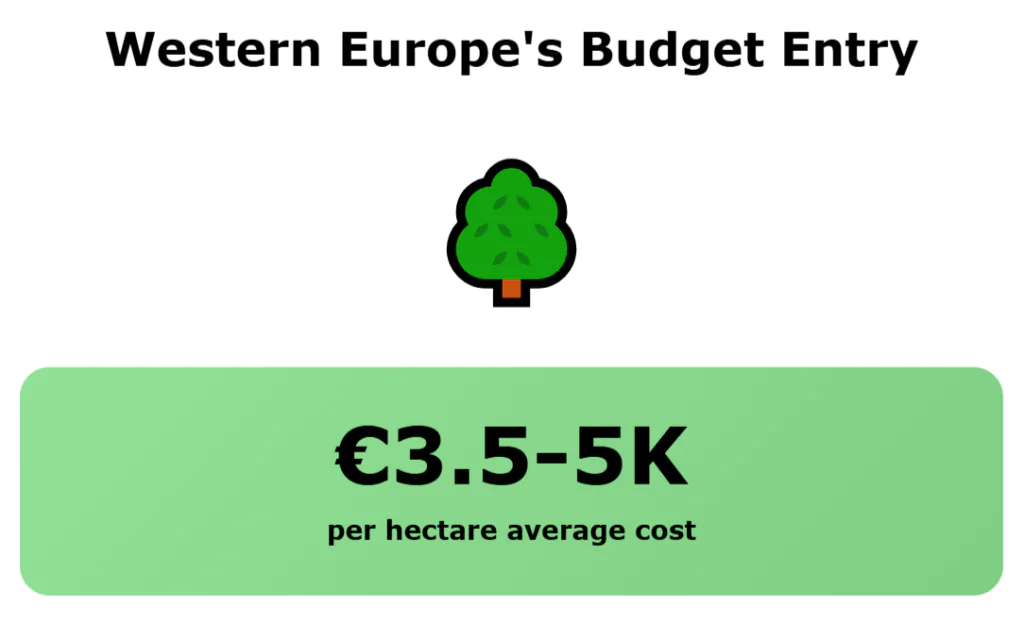

Number 8: Green Bocage

Haute-Vienne gives you one of the cheapest entry points into Western Europe’s green cattle country: Limousin.

Land prices here average about €3,500 to €5,000 per hectare. That means less than US$2000 per acre; cheaper than North Dakota. At that level, you can buy enough ground for a real farm, not just a garden.

The landscape is classic bocage: small fields, hedgerows, streams, and a lot of chestnut trees. Rainfall is reliable enough that many livestock farms run with no irrigation. The farming turns around cattle and chestnuts.

Limousin cattle are France’s flagship beef breed. Most farms use grass and hay from permanent pasture, with some maize or other forage. Chestnut groves add a second line of income and diversify risk.

The Cons? The soil is acidic. If you want to cultivate cereals, likely you will need to use techniques like spreading lime.

On top of that, the SAFER public agency can block your purchase if you come in as a hobby buyer, without a serious project. To access subsidies and sell to big cooperatives, you usually need the Capacité Agricole certification or an accepted plan. So yes, this part of France has low prices and decent land quality, but some bureaucracy.

We are halfway through the ranking, and soon I’m planning a dedicated ‘A-to-Z’ buying guide for a specific European country. If you have a preference—Italy, Spain, France, Portugal—let me know in the comment section; you will decide my next content.

Number 7: Cork Trees and Long-Term Payouts

There is a part of Portugal where trees pay you about once a decade.

That place is Interior Alentejo, around Évora. Évora, the main urban center, has close to 55,000 residents and provides hospitals, schools, and services for the wider rural area. Land prices in Interior Alentejo usually range from €7,000 to €11,000 per hectare.

The range reflects three hard variables: the maturity of cork oaks, water access, and overall land quality. A block with 40‑ to 60‑year‑old montado and a licensed borehole falls at the upper end. Young trees or no water drag the price down because income arrives later and risk climbs.

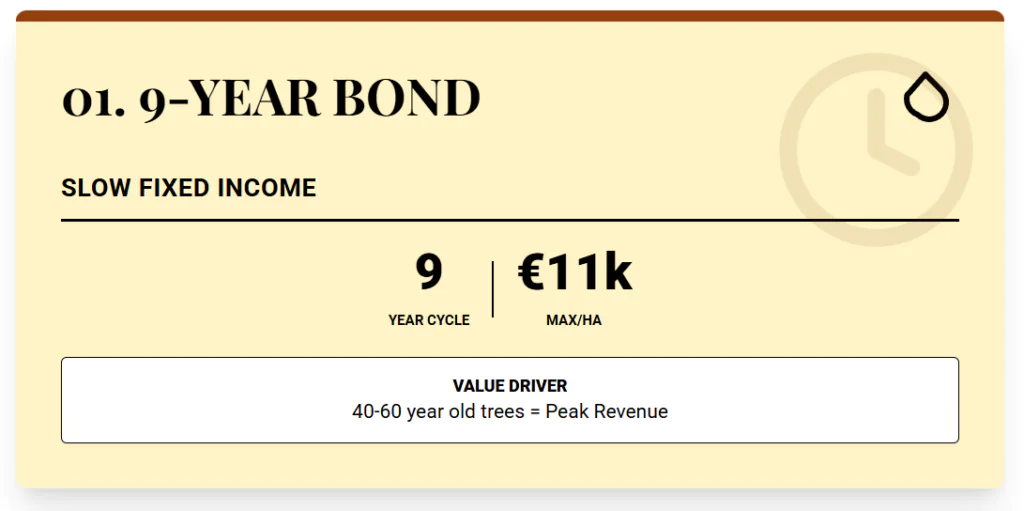

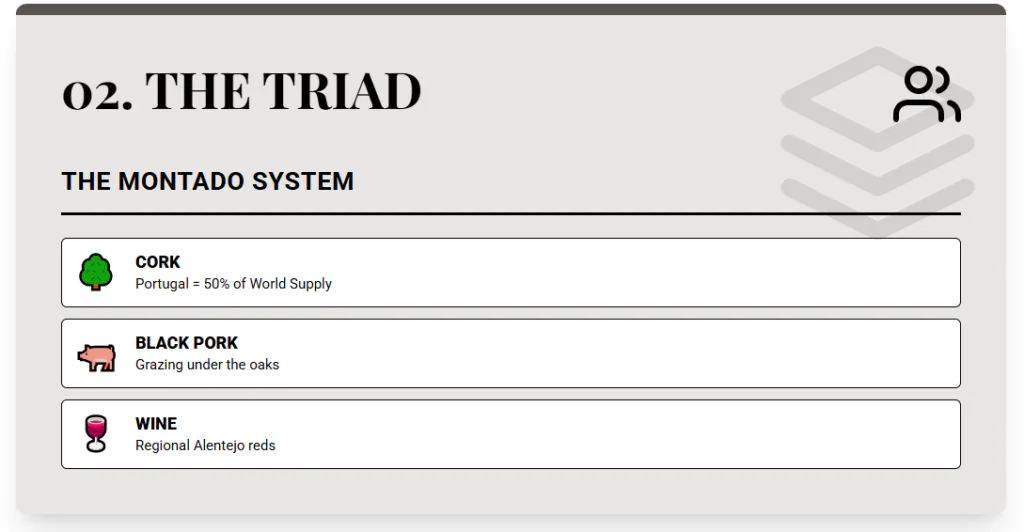

The core farming cultures are cork, black pork, and wine. You harvest cork about every nine years. One harvest brings a large cash injection with relatively low ongoing work; like a fixed income bond at its maturity.

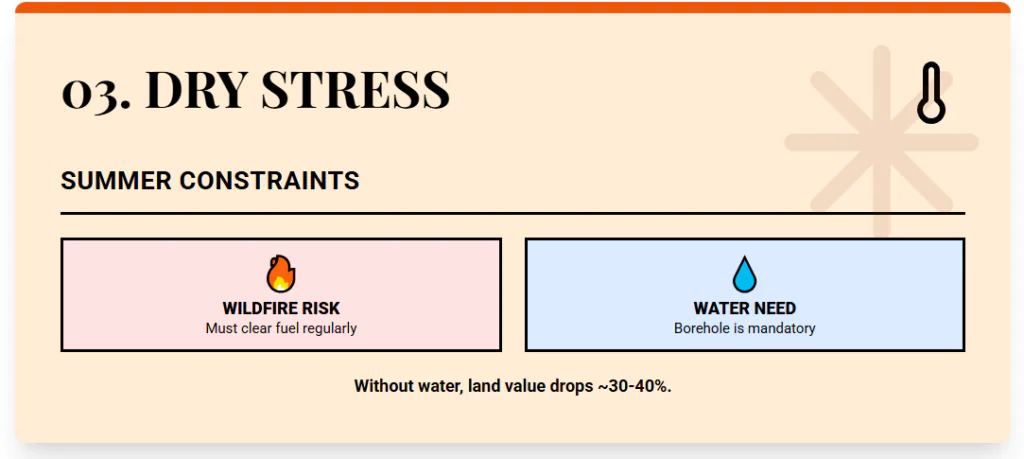

Heat and water are the main constraints. Summers run hot and dry, and during dry years, it is necessary to have alternative water sources. Dense vegetation and dry weather also lift wildfire risk, which raises insurance costs and forces regular fuel clearing.

Foreign buyers follow a clear process: get a Portuguese NIF, use an advogado for checks, and sign at the notary.

Number 6: High-Yield Plains for Bold Buyers

If you want some of the cheapest high-yield land inside the EU, you end up in North East Bulgaria, around Dobrich.

Land prices here often range from €2,000 to €3,500 per hectare. On this list, that is the lowest arable price band. This is the equivalent to US$1200 per acre; a price similar to Montana in the US.

At that cost, you can buy scale and still keep capital free for machinery, storage, or irrigation. All that on the Danube and Black Sea plains, with very productive soils. The main farming cultures are sunflowers, wheat, and corn.

On top of that, the area has become a new frontier for lavender, and Dobrich is part of that shift. There is also strong potential for organic honey, because many abandoned zones lack industrial pesticides, which helps bee health. To purchase land, non‑EU buyers need to create a Bulgarian limited company.

Setup costs usually fall between €600 and €1,000, and yearly costs are around €500 to €1,000. You also deal with weak infrastructure in rural areas. Roads can be in poor condition and electricity supply can be unstable, which raises operating costs while depopulation reduces the labor offer.

Compared with other Bulgarian regions, Dobrich has better soils, closer access to ports, and stronger integration into export routes through the Danube and Black Sea. At €2,000 per hectare, Bulgaria is the price floor of this ranking, but believe it or not, you can go cheaper in Europe if you are willing to take on more risk.

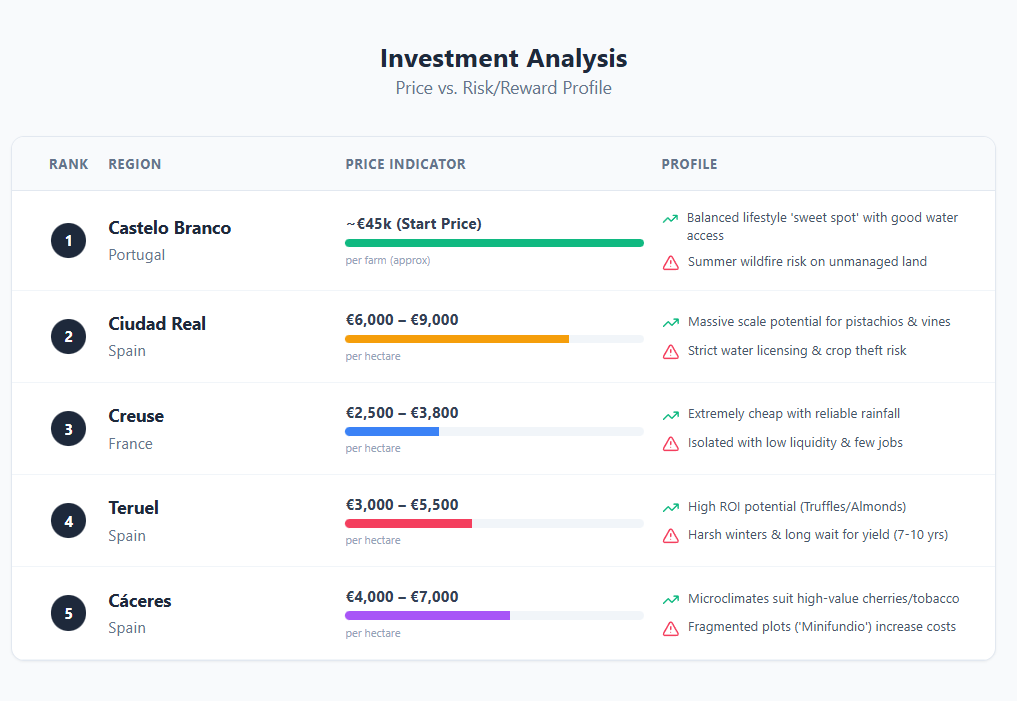

Number 5: Microclimates, Cherries, and Unusual Parcel Maps

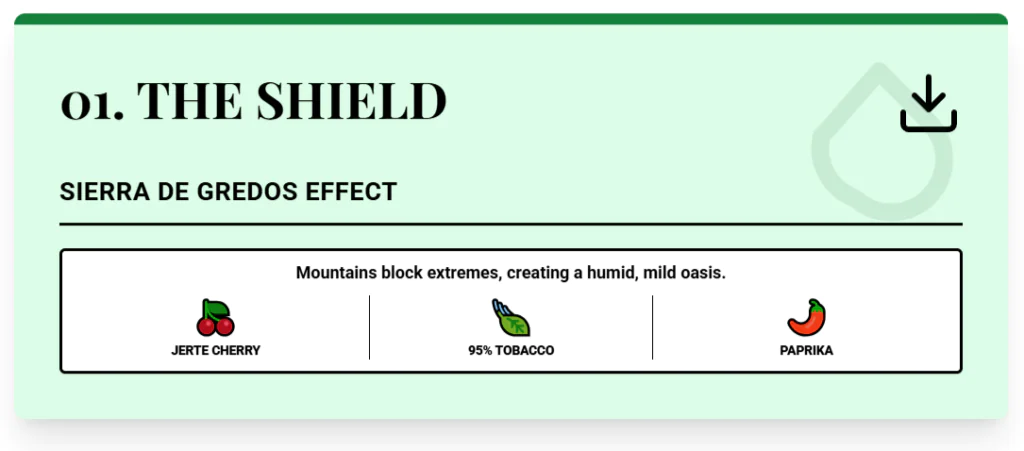

Cáceres gives you one of the most interesting microclimate plays in Western Europe at mid-range prices.

In those valleys, the Sierra de Gredos mountains block extremes. You get mild conditions that allow crops that fail in hotter southern zones. Tobacco grows there: Cáceres produces about 95% of Spain’s tobacco.

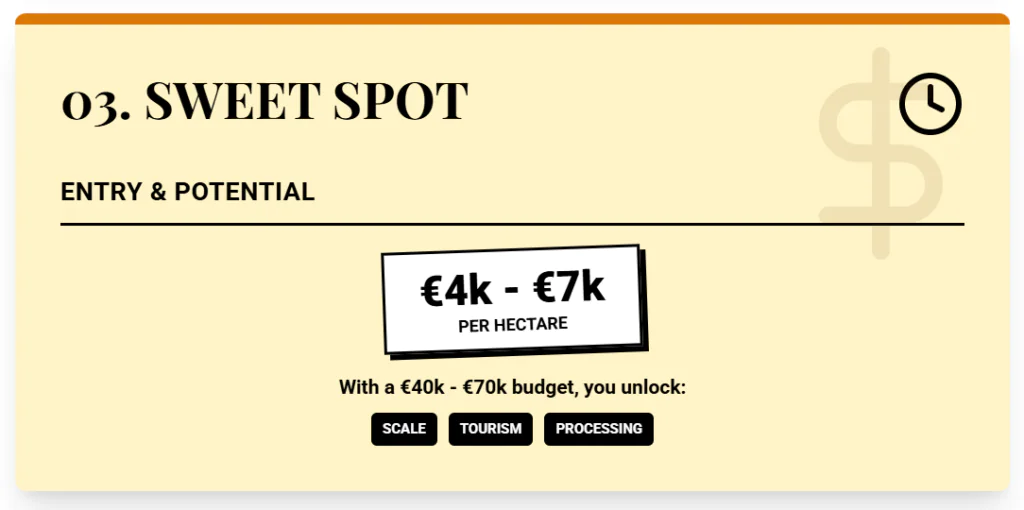

In the same area you have Pimentón de la Vera, a protected paprika, and in the Jerte Valley, millions of cherry trees that feed a high-value fresh fruit and processing sector. Land costs around €4,000 to €7,000 per hectare. That means an average of US$2500 per acre, a price similar to Oklahoma.

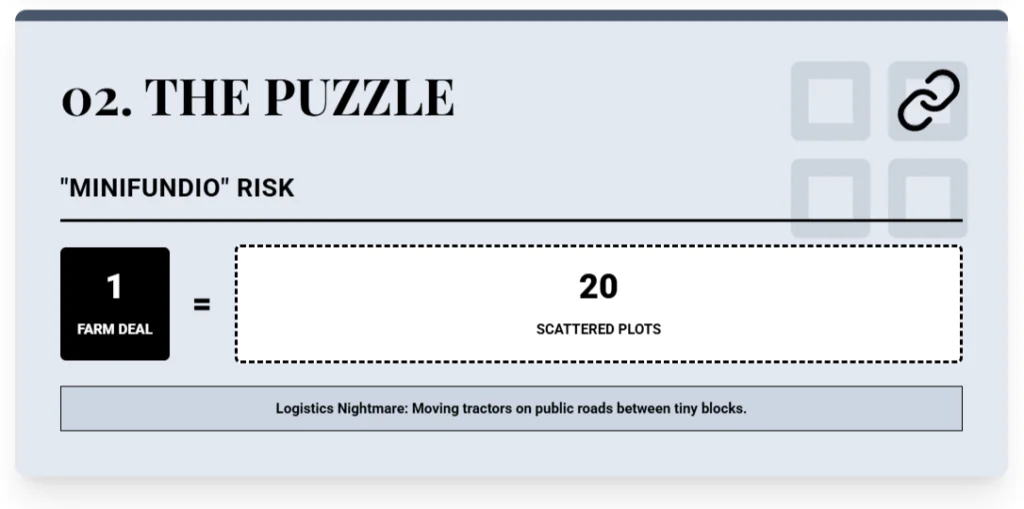

At €40,000 to €70,000 you already talk about 10 hectares on the cheaper band, which you can split between cherries, paprika contracts, and guest units if your project allows. The structural problem is “minifundio.” A “5-hectare farm” can mean 15 or 20 scattered plots.

You might negotiate with several owners, rebuild boundaries, and move tractors on public roads between blocks. Fencing, access tracks, and consolidation add real cost. Near protected rivers and mountain areas, environmental rules limit new buildings, earthworks, or tree clearing.

Tourism already brings hikers, food travelers, and cherry-blossom visitors.

Number 4: Truffle and Almond Patience Play

Can you turn a cold, depopulated plateau into a high‑value farm just by planting the right trees and waiting?

Teruel, in Aragon, is where we can find the answer to that question. Land prices here usually range from €3,000 to €5,500 per hectare. At those levels, you enter a climate with colder winters, dry air and limestone soils with a pH around 8.

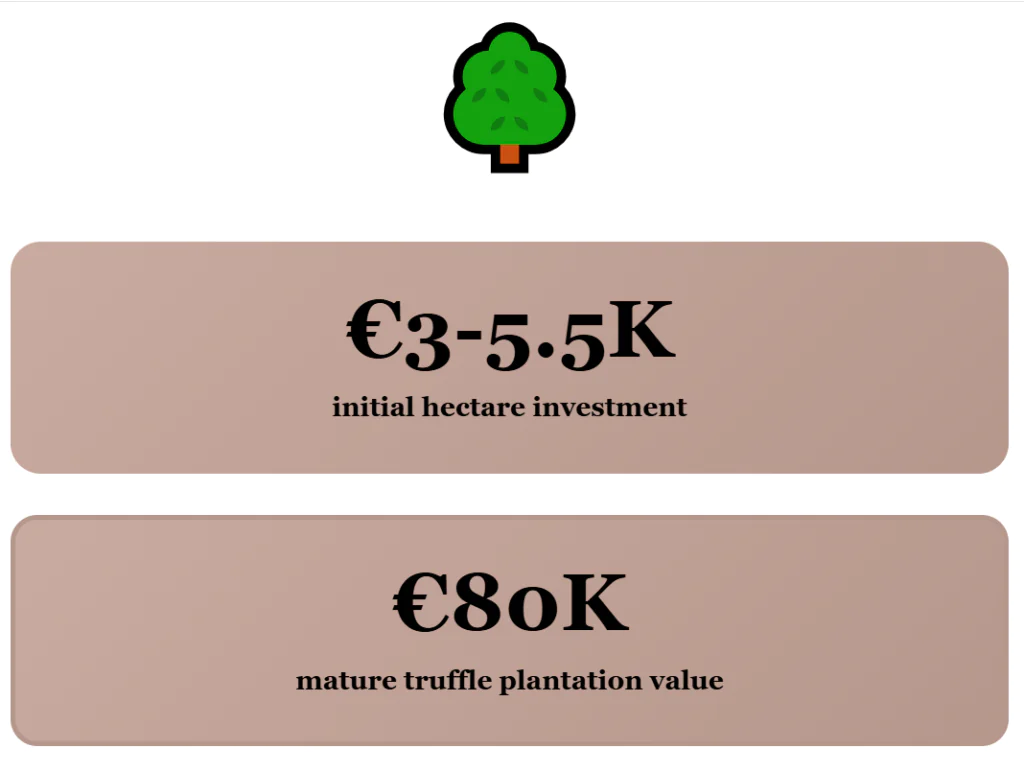

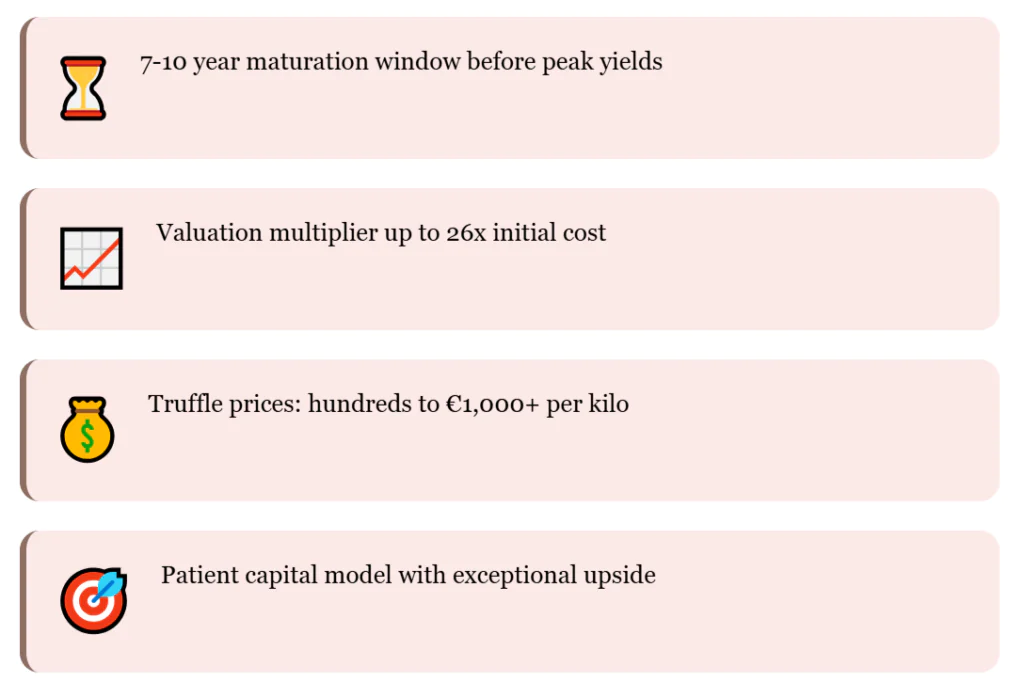

That mix is not good for soft crops, but it is ideal for two specific ones: black truffles and almonds. Black truffles, Tuber melanosporum, drive most of the upside. Truffle oaks need 7 to 10 years to reach peak production, so you put money down long before you see income.

The payoff can be big. Once plantations reach full production, land values can rise to as high as €80,000 per hectare. Truffle prices often reach several hundred euros per kilo, and in some seasons go over a thousand.

Almonds are the second pillar. Farmers use late‑blooming varieties to dodge spring frosts, which are common at this altitude. The climate cuts both ways.

Cold winters and dry air reduce pest pressure, so you use fewer pesticides and can target organic markets. But the same cold brings frost risk. On the lifestyle side, Teruel is part of “empty Spain.”

Depopulation, sparse services, no high‑speed rail, and hard winters mean you do not move here for a busy social life. Spain responds with tax breaks and incentives for investors who set up in these areas. That turns Teruel into a place for patient farmers, with a chance of large gains once truffle and almond plantations mature and start to prove their value.

Number 3: Cheap, Green, and Built for Neo-Peasants

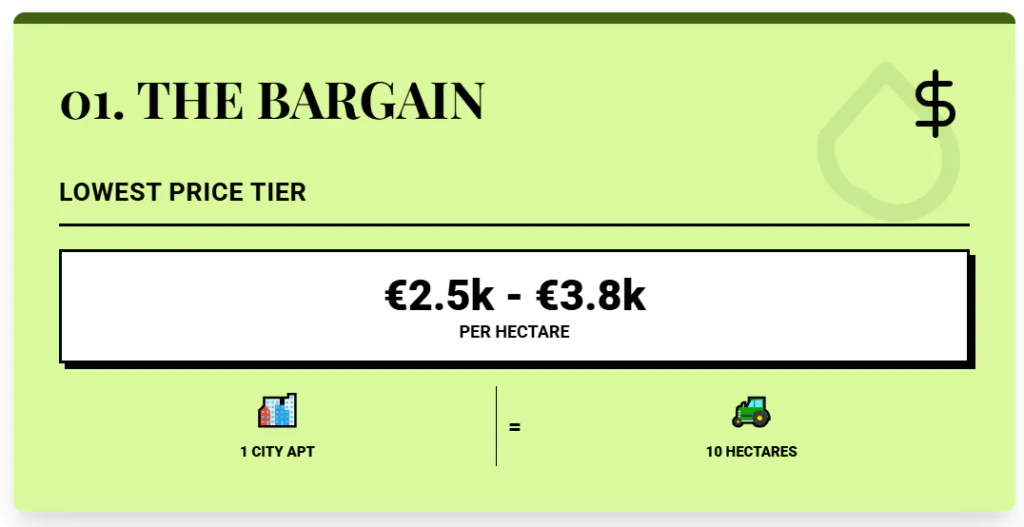

Creuse, in the region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, is one of the cheapest rural departments in France.

Land prices range from about €2,500 to €3,800 per hectare. At those prices, you can buy 20 hectares (50 acres) for the price of a studio in a big city. The climate works in your favor if you want grass-based farming.

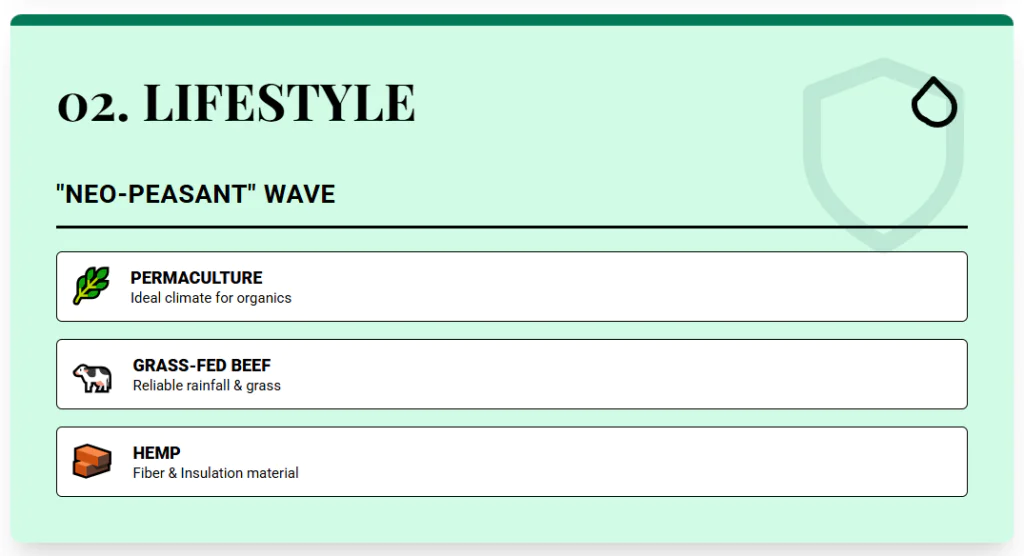

Rainfall is reliable, water sources are common, and the temperatures support grass-fed beef and permaculture systems. Cattle is the main farming culture here, and it is often grass-fed. Low land prices have pulled in a steady expat wave.

You see people from the Netherlands, the UK, Belgium, and other countries buying farmhouses with land. Many of them form part of a “neo-peasant” movement: small organic or mixed farms, direct sales, and self-sufficiency projects. They are also known as ‘former IT managers after a burnout’.

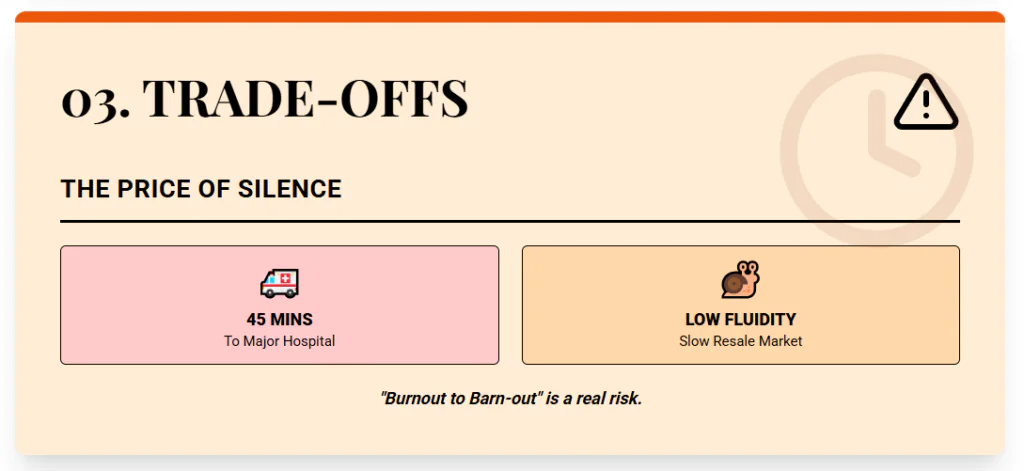

As with the other places, there are some downsides in this region. Medical infrastructure is limited. For specialized hospitals, you may drive up to 45 minutes.

Job options outside farming are uncommon, so most newcomers either farm, work online, or commute. Liquidity is another hard factor. Because the buyer pool is small, the population is dropping, and many locals already own land, properties can take longer to sell.

If you think you might need to exit quickly, you must treat that slower resale speed as a real risk. SAFER also operates in Creuse, but due to the depopulation issues, it tends to be more open to lifestyle buyers. That combination of low prices, water availability, and less regulatory pressure is what gives Creuse one of the best “quality-of-life per euro” profiles in Western Europe.

Number 2: La Mancha’s Big-Field Pistachio Engine

This region quietly turns hundreds of hectares of dry plains into pistachios, vines, and cash flow.

We are in the province of Ciudad Real, in the autonomous community of Castilla-La Mancha. Around it, you get wide, red plateaus that favor very large, machine-friendly parcels. Land prices usually range from €6,000 to €9,000 per hectare, and that spread mainly reflects one thing: whether the land has legal water rights.

The core farming cultures here are pistachios, vineyards, saffron, and cereals. Hot summers, cold winters, and low humidity match what pistachio trees need. That is why this area has become one of Spain’s main pistachio engines.

Land with productive pistachio trees can raise the land prices to €9,000 per hectare and beyond. And that is because Pistachios use less water than almonds and sell at high prices. Vineyards add another layer.

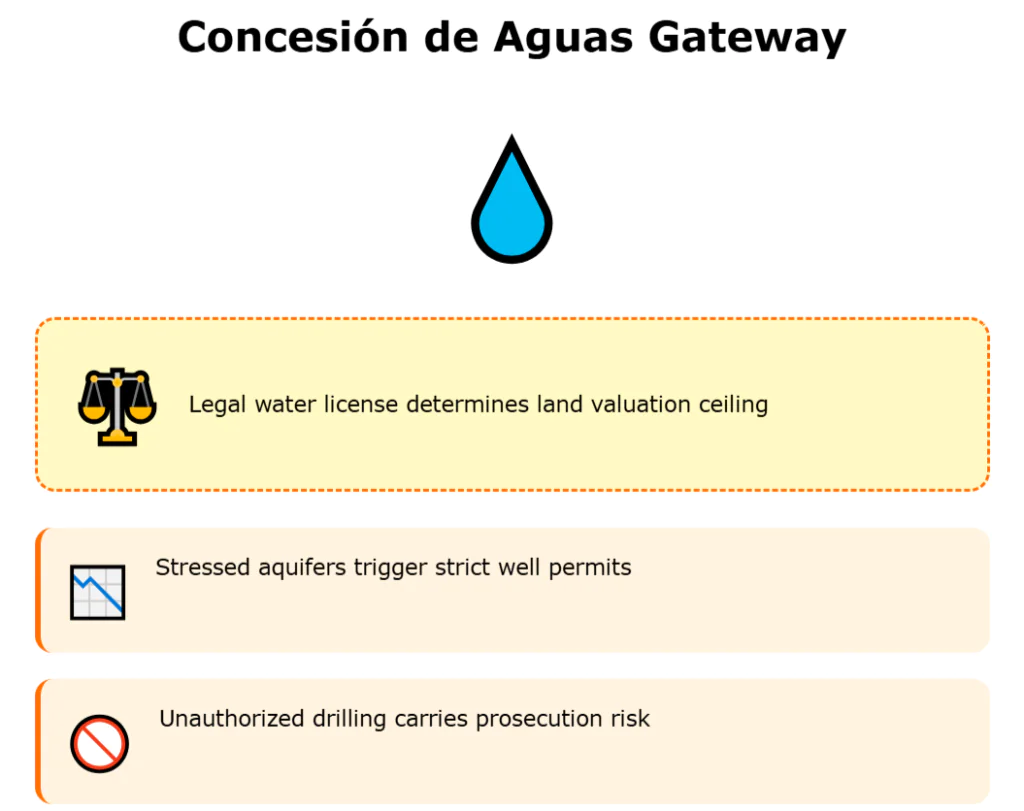

Ciudad Real forms part of the La Mancha DO, the largest vineyard surface on the planet. That scale makes it interesting if you want to blend grape production with cereals like barley and wheat, using the same machinery base. Water licensing is the main tension.

Aquifers here stay under pressure. New wells face strict limits, and illegal drilling carries real risk. Land without formal water rights can be hard to use for pistachios or vines at scale, and that pushes its value down toward dry cereal use only.

Security is the second friction point. Pistachio theft has grown into a “crime wave.” So investors spend on perimeter fencing, cameras, guards, and better tracking of harvest and storage.

Spain is an “Open Door” country, so as a non‑EU buyer you can purchase farmland directly, as long as you get an NIE and use an abogado for checks. Ciudad Real suits serious medium‑to‑large investors who want scale and high‑value crops and who treat water rights and security as core line items, not details. And now, finally, we arrive at the region that checks more boxes than any other for non‑EU buyers and small farmers.

Number 1: The Benchmark Sweet Spot

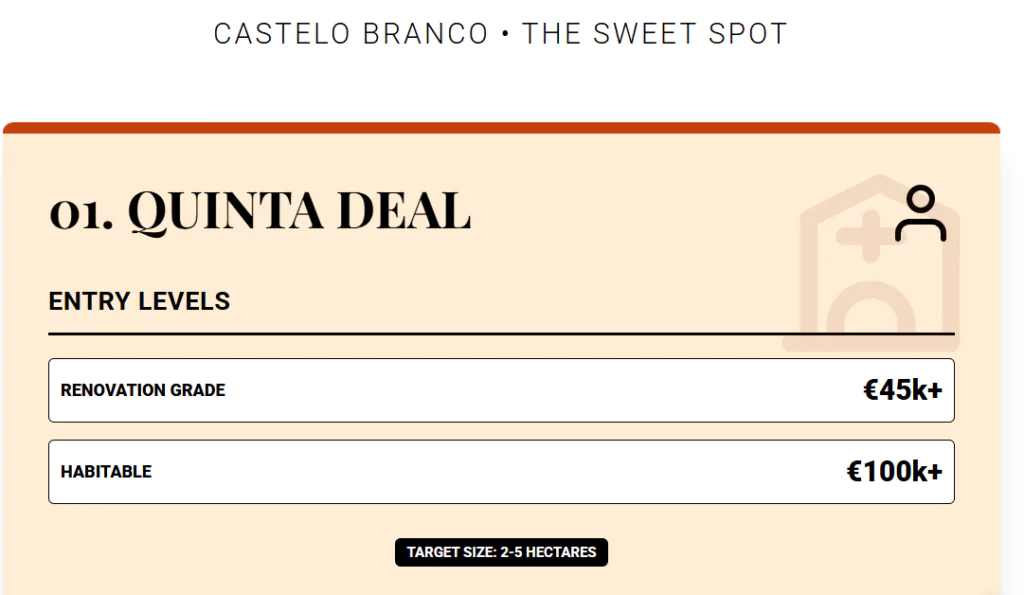

This is “quinta country.”

You mostly look at 2–5 hectare farms with stone houses, often granite, and old olive or fruit trees already in place. Renovation‑grade quintas start around €45,000. Small, habitable quintas with land often land near €100,000.

You can still find 10 hectare quintas for lower prices than a mid‑range city apartment. The farming cultures are olives, mixed fruit, small vineyards, and self‑sufficiency plots: vegetables, chickens, goats, and some honey. Water is the big advantage.

You have the Zêzere River, several dams, and a better water outlook than the Algarve or Alentejo coasts. Many properties already have a well or borehole. But summer wildfires threaten poorly managed land, while winters can bring freezing nights.

On the bureaucracy side, the path is clear. You get a Portuguese NIF, often online for about €150 with a fiscal representative. That low bureaucracy, the amazing prices, plus the good access to water are the factors that put Castelo Branco in the top spot of European farmlands for good prices.

Now, I have made another ranking of the absolute cheapest places to buy farmland in Europe – some of them are quite cold, but the prices are unbeatable.

And join my Patreon for all the sources and charts from our articles, plus a chat, so I can answer your questions. Tier 2 includes all my eBooks on living and retiring abroad-scan the QR code today!

Levi Borba is the founder of expatriateconsultancy.com, creator of the channel The Expat, and best-selling author. You can find him on X here. Some of the links above might be affiliated links, meaning the author earns a small commission if you make a purchase.