The retirement crisis is driven by declining birth rates and increasing life expectancy, leaving fewer workers to support a growing elderly population. Compounded by stalling productivity and high government debt, state pension systems are becoming unsustainable. To protect yourself, prioritize investments in resilient assets and consider retiring in countries with better economic demographics.

Are State Pensions at Risk? The Short Answer Is Yes. The Long Answer Is Below.

Is the State Pension System Actually a Ponzi Scheme?

State pensions have been in a state of decline for the last few decades. A retirement crisis is coming. There are 3 reasons leading to not enough young people to contribute and fund the pensions of the older generations.

There is a thing most people don’t get about social security: when you retire, you will not use the money that you contributed. Your contributions will be long gone, paid to your grandparents or parents. Who will pay for your retirement?

The next generation. Our kids. But how many kids do we have?

The decline in birth rates is widespread all over the world, but in countries where women still have over 2 children, there is a chance to save public pension systems from the coming retirement crisis.

This is not the case in Europe, America, or most of the western world. In 2019, the European Union had a crude birth rate (the number of live births per 1 000 persons) of 9.3. For comparison, the same rate was 10.5 in 2000, 12.8 in 1985, and 16.4 in 1970. This is a 44% drop in less than fifty years.

Ps: If you are interested in retiring abroad, our consultancy’s team wrote a few articles about hot retirement destinations, such as:

How Severe Is the Retirement Crisis in Western Countries?

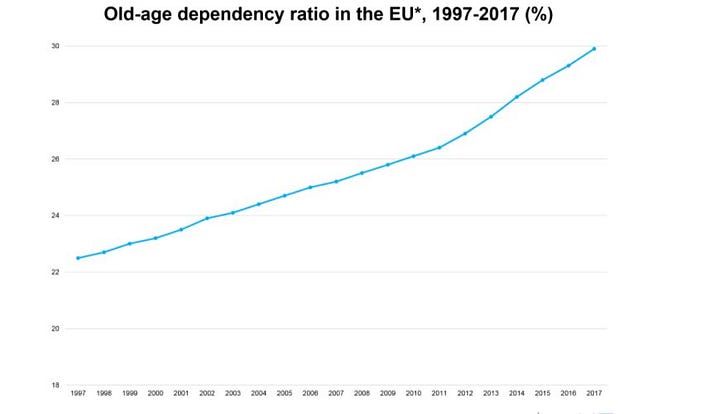

The old-age dependency ratio indicates the level of support available to older people (65 or over) by the working-age population (between 15 and 64). It means how many pensioners (or potential pensioners) exist in proportion to pension contributors.

According to Eurostat, in the EU, the old-age dependency ratio was 29.9% in 2017. In other words, there were slightly over three potential contributors for every person aged 65 or over. The EU’s old-age dependency ratio has been increasing for a long time, as shown below:

| Time Period | Workers per Pensioner (Approx.) |

|---|---|

| 20 Years Ago | 5 to 1 |

| 10 Years Ago | 4 to 1 |

| Today (2017 Data) | 3 to 1 |

The chart below shows that the proportion of elders to working residents increased from 22.5% to 30% in less than 20 years.

In other developed countries, it can be even worse. In Japan, the old-age dependency ratio is close to 50%.

This is not viable. The definition of a Ponzi scheme, according to the Investopedia, is:

Ponzi schemes are investment cons that work on the premise of “Robbing Peter to pay Paul.” They may not necessarily adopt a pyramid scheme’s hierarchical structure, but they do promise high returns to existing investors by taking investment money from new blood. Often lured by the prospect of too-good-to-be-true returns, most Ponzi participants end up losing everything.

Just like in the Ponzi frauds, the public pension system works by forcing the new entrants to pay the returns of the previous adopters. It is Bernie Madoff upgraded to a global scale.

The only reason that this entire scheme didn’t implode yet is that it benefited from a few favorable situations.

- The demographic dividend

- Productivity gains from education fulfillment

- Leeway for increasing government debt

These 3 support beams held — until now — the fragile structure of global public pensions. But they are crumbling. At the same time.

The demographic dividend is over

The demographic pyramid has this name for a reason: during most of history, it had a pyramidal shape, with the base larger than its middle part. Throughout the entire human existence, nations always had a far larger share of younger people than elders.

Except for the last few decades.

Decreasing birth rates and increasing life expectancy turned pyramids into weird towers with their middle sections far larger than the base, signaling next decades with fewer taxpayers to support more and more pensioners.

The image below shows how the Finnish demographic pyramid changed over the last 70 years. We observe the same changes in multiple countries.

When current workers retire, there will be less money to support them. One could say that the increase in productivity can avoid this negative scenario.

But here is the next bad news.

The productivity gains from education fulfillment are gone

The US and most developed countries reached a plateau in educational fulfillment. It is getting harder to increase workforce productivity by adding more college years.

While the productivity gains from transforming an illiterate farmer into an agronomist technician are considerable, the difference between an undergrad and a graduate is often marginal.

Besides, when a country achieves widespread high levels of instruction, the cost of higher education skyrockets. As pointed by Robert J. Gordon in his paper Faltering Innovation Confronts The Six Headwinds:

This combines several problems. One is the cost disease in higher education, that is, the rapid increase in the price of college tuition relative to the prices of other goods. This cost inflation in turn leads to mounting student debt, which is increasingly distorting career choices and deterring low-income people from going to college at all. Not everybody gets a scholarship.

Talking about debt, there is the 3rd, and most dangerous, of all the collapsing pillars: government debt.

The burden of government debt will fall over our heads.

Government debt increased steadily over the years everywhere except for special cases, like oil-rich nations.

For decades, states funded public pensions by taking loans. This is especially common in democracies since changing the rules of retirement is highly unpopular and can switch electoral results.

But, with time, there is a reduction of the government’s ability to roll over debt. Once that happens, there are two options:

- Government increases taxes so to pay part of the debts. This may be a solution for countries with still low tax-to-GDP ratio, like Ireland (22%) or Singapore (14%), but hard to imagine in places where taxes take almost half of the entire gross domestic product, like France or Denmark.

- The government increases the retirement age to reduce the money spent on the public pension system. This is the most likely solution to be adopted by Western, developed countries.

We are the ones who will pay off our government’s debts through taxes, inflation, and delayed (if ever happening) retirement.

How to survive the coming retirement crisis?

All it takes is a few bad economic years and all the money accumulated in public pension funds may disappear, leaving only debt behind.

Some optimists think innovations may solve this disaster. Things like artificial intelligence or robotics, who would compensate for the shrinking birth rate.

However, the automation productivity increase will fill only a few pockets, funding the pensions of a pool of billionaires.

Here is what I do to avoid the trap of relying on public pension schemes and escape the retirement crisis. No magic solutions though, because they don’t exist.

- Give preference to investments in antifragile assets, managed by executives with skin in the game (a rarity nowadays).

- Invest also (but not only) in emerging countries, where the demographic dividend is still going strong. When investing in emerging economies, be aware of their peculiarities.

- Avoid declining industries. If it may not exist in 2030, it is a bad deal.

- Prefer investments in sectors that will benefit from rising prices, because inflation is coming.

- Don’t listen to economists and run away from destructive investment fallacies.

- Avoid exposure to ruin through geopolitical risks, especially at a time when governments are again issuing war survival guides.

- Consider the possibility of moving to countries attractive for retirement. There is an entire guide about how to retire in Bali and another about how to retire in Jamaica.

Levi Borba is CEO of expatriateconsultancy.com, creator of the channel Small Business Hacks, and best-selling author. You can check his books here, his other articles here, or his Linkedin here.