This is Mr. Graham, from Phoenix, Arizona.

He bought a gorgeous apartment in Europe.

Then the letter arrived: a new law required an immediate, expensive energy retrofit. His savings were wiped out.

I’ve guided hundreds like you through Europe’s real estate traps, and the rules are changing faster than ever – so today I will expose the five worst countries to buy a home in Europe.

- I will show you the country where you can’t freely rent out your own property.

- I will cover a country where rental returns are just 1.5% per year, so your property will barely pay for its own expenses.

- And I will get to the country that all but bans foreigners from buying residential real estate.

This isn’t about scaring you; it’s about alerting you about forced upgrades, rent controls, or staggering taxes on your property.

We from The Expat did the research and ranked the five most problematic countries so this doesn’t happen to you. Let’s dive in because the two worst ones might surprise you.

The Criteria

For this ranking, I considered four specific factors that directly impact you as a foreign buyer. These aren’t about opinions; they are about the hard numbers and laws on the ground.

First is Regulatory Burden. This is where the government actively works against you as a landlord. It includes rent controls that put an artificial ceiling on your income, regardless of market demand. It also covers laws that force you to perform expensive, mandatory upgrades on your property just to be allowed to rent it out, draining your capital for zero additional return.

The second factor is Tax Friction. I look at the total tax impact that chips away at your investment, upfront transfer taxes and notary fees that can consume a huge chunk of your initial capital. In France, for example, notary fees alone on older properties can reach 7% to 8% of the entire purchase price.

Third is Yield Compression. This is a critical issue in over-regulated markets. It’s what happens when property prices are pushed higher, but rental income is held down. Your rental yield, which is your annual rental income as a percentage of the property’s value, gets squeezed so tight that the returns might not even cover your taxes and maintenance.

The final factor is Absolute Barriers. These are the straightforward laws that outright ban or severely restrict you, as a non-resident, from buying property at all. Now you understand the criteria. Let’s start with the country that is bad, but not the worst on our list.

Number 5: Portugal — The Trap of Policy Volatility

Portugal appears on countless ‘best places to live’ and ‘best places to retire’ lists. So you are right to ask why it is number five on our list of the worst countries to buy property. The reason is policy volatility.

In Portugal, you are investing in a country where the government can, and does, change the fundamental rules of the game with almost no warning.

We saw a prime example of this when the government abruptly terminated the popular Golden Visa program for real estate investments. This single decision did not just change future rules; it stranded thousands of applicants who were already deep in the process. The message was clear: a program that drove billions into the economy could be dismantled without a second thought.

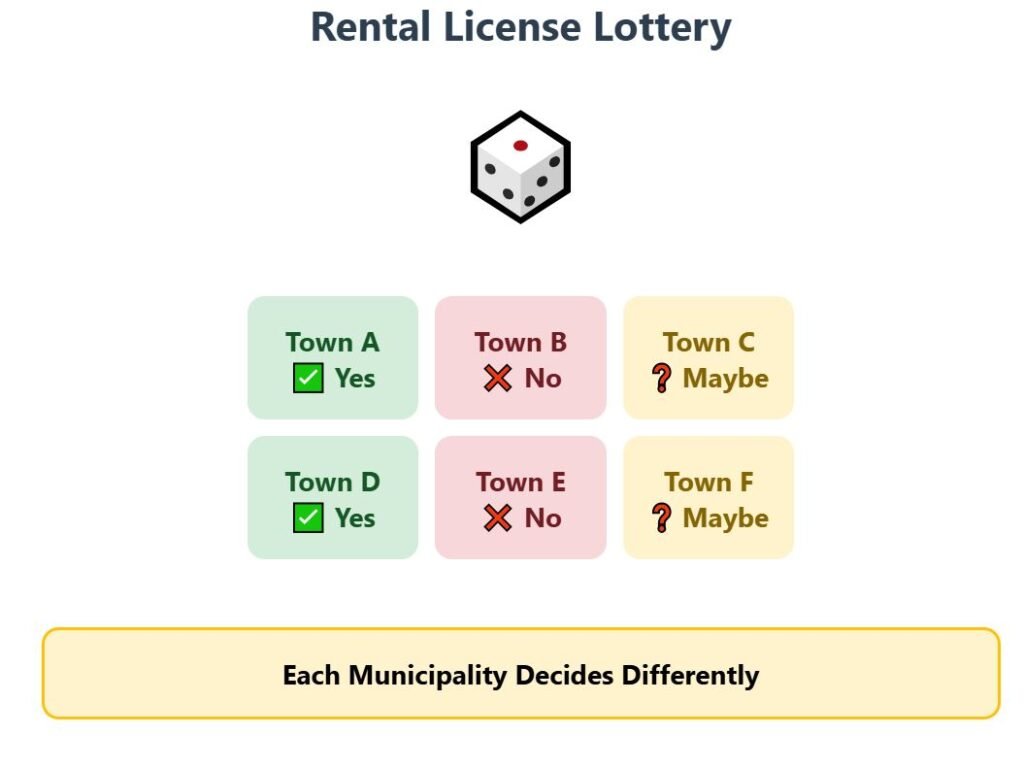

Then, the chaos shifted to short-term rental licenses, known as Alojamento Local, or ‘AL’. First, the central government announced a nationwide suspension of all new licenses in most areas, instantly threatening thousands of property owners who relied on tourist rentals. After significant backlash, they reversed course and cancelled the restrictions, but… Instead, they pushed the decision-making power down to local municipalities.

This means your ability to get an AL license and legally rent your property to tourists now depends entirely on the shifting political priorities of a city council. A council in the Algarve might be pro-tourism and grant licenses, while the one in the next town might impose a complete ban.

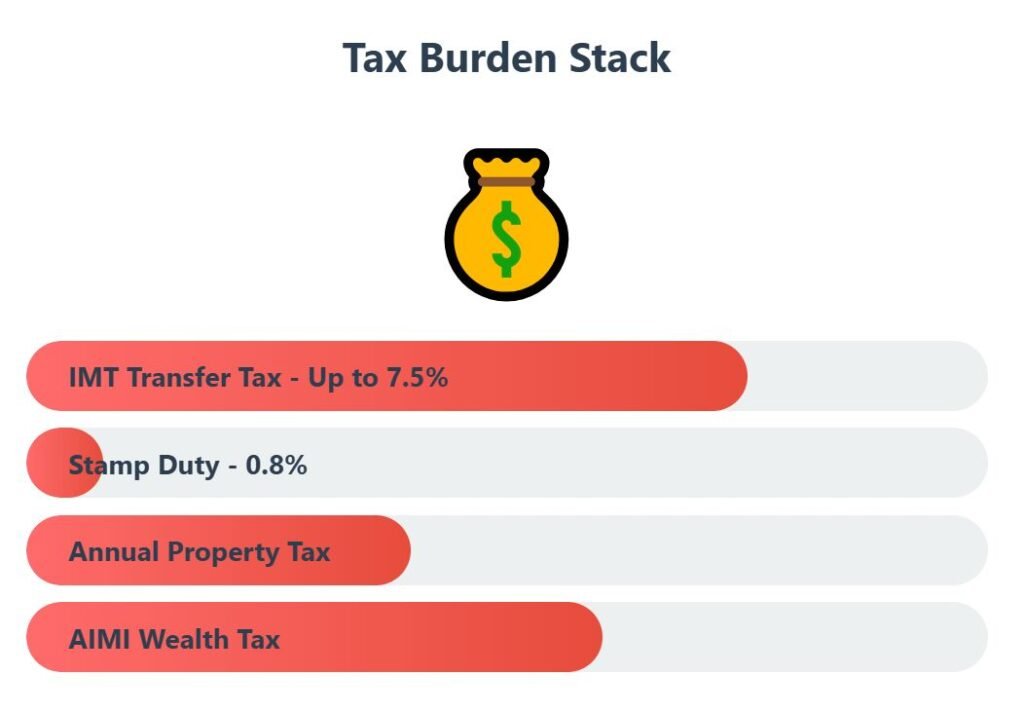

On top of this regulatory instability, you face significant tax friction. When you buy, you pay the IMT transfer tax, which is a progressive tax that climbs to 7.5% for higher-value properties. You also pay a 0.8% stamp duty. After the purchase, you face an annual municipal property tax. And if your property portfolio in Portugal exceeds a certain value, you are hit with an additional tax called AIMI, which functions as a pure real estate wealth tax.

While the lifestyle appeal in Portugal is undeniable, the investment framework is built on sand. When you invest in Portuguese property, you are betting against future government intervention. For a prudent investor looking for stability, that is a high-risk bet.

Number 4: Germany — The Unpaid Tenant

Germany is Europe’s economic engine. But the entire German system is built on a foundation of tenant protection. The central issue that defines the German rental market is a policy called the ‘Mietpreisbremse’, or rent brake. This is the law in hundreds of German municipalities, including all the major cities where you would likely want to invest.

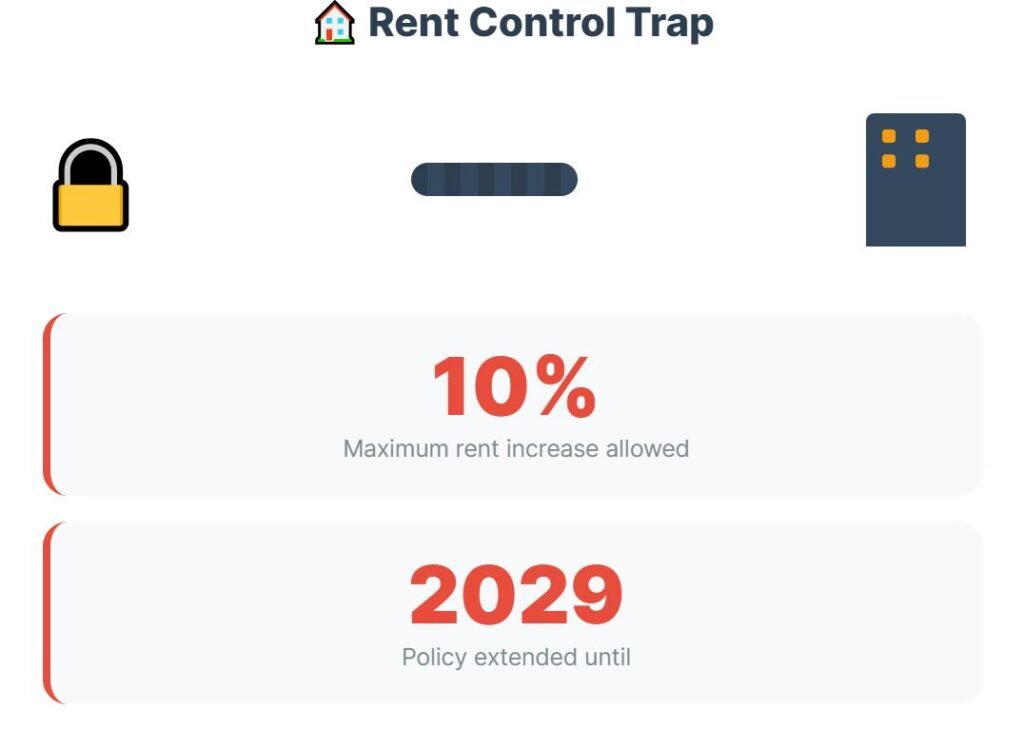

When you sign a new lease, this law caps the rent you can charge at just 10% above the official local rent index, known as the ‘Mietspiegel’. This index is a detailed survey of existing rents, effectively anchoring new contracts to old prices.

The German government has already extended this law until 2029, signaling a long-term commitment to this policy. Your potential upside is simply removed by law – that is why, in some cities, the number of new constructions dropped. And if your tenant does not pay rent, and you must file for an eviction process, get ready for a long marathon that can take years. In Germany, to evict a tenant is very, very hard – even if he refuses to pay.

This is what a specialist from Berlin told us:

“Once you sign a contract with a tenant, the tenant virtually owns the apartment, and you might never get it back. Prospects of ever raising the rent are very limited. And if you decide to sell the property, the tenant will remain inside, which also means that the value is around 30 % less than a vacant apartment. Also, the tenant can easily sue you to lower the rent too. And people wonder why there is a lack of supply of rental apartments…”

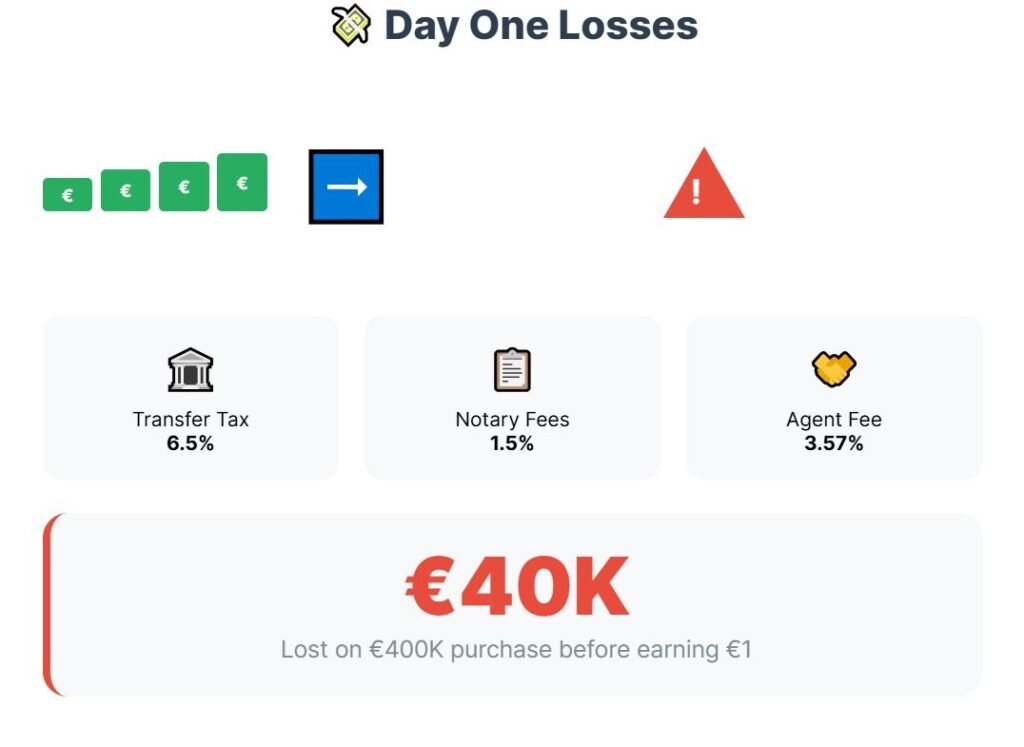

The restrictions don’t stop at very, very hard eviction processes. Then you have a massive barrier to entry in the form of transaction costs. Before you earn a single euro in rent, you lose a significant percentage of your capital.

The real estate transfer tax, or ‘Grunderwerbsteuer’, varies by state and can be as high as 6.5%. Add to that notary and court registration fees which are around 1.5%. Then, factor in the buyer’s agent commission, which is around 3.57%. When you combine these, on a 400,000 euro apartment, that’s over 40,000 euros gone on day one.

And there are other restrictions: many cities, including Berlin, Hamburg, and Munich, enforce ‘Zweckentfremdungsverbot’ laws. These are strict regulations that can ban or severely restrict you from using your property for short-term rentals on platforms like Airbnb.

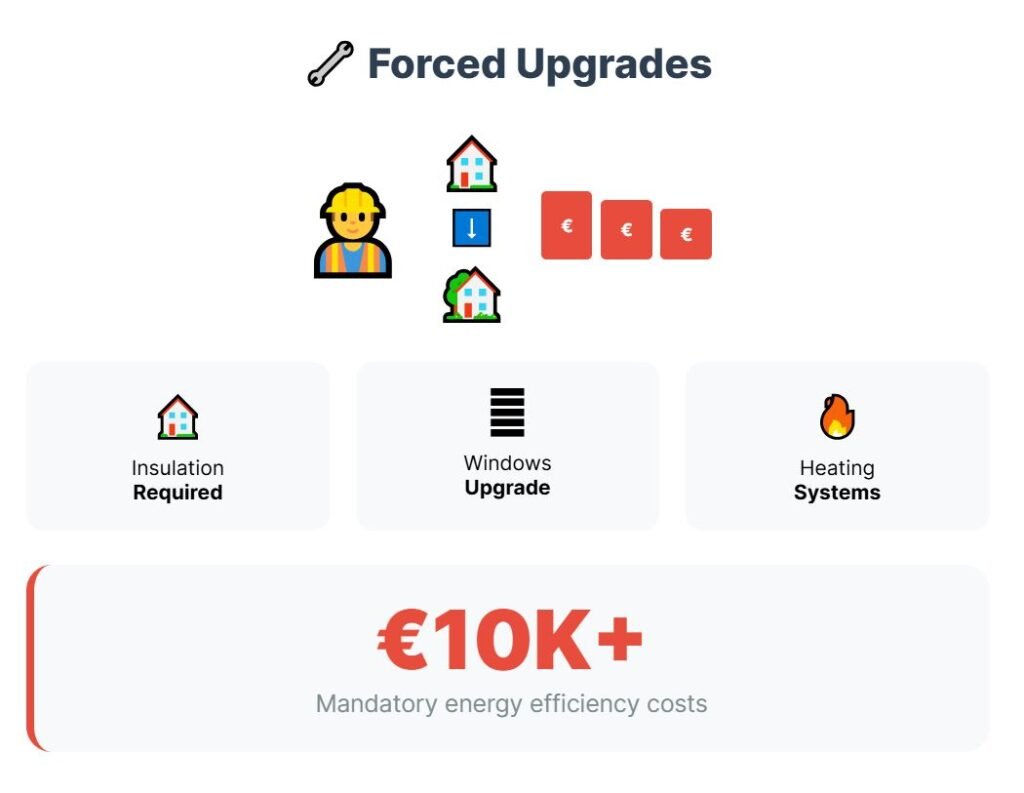

On top of these income caps and usage restrictions, there is a growing layer of mandated expenses. Germany is aggressively pushing for energy efficiency renovations in its building stock. This means as an owner, especially of an older building, you can be legally required to spend tens of thousands of euros on upgrades like new insulation, windows, or heating systems.

PS: I have some really good news: FREE FOR A LIMITED TIME: Grab your Expat Wealth & Lifestyle Compass ($108 value) today! Includes our 74-page guide of Affordable European Cities, our Zero-Tax countries report, and our expat checklist. http://patreon.com/The_Expat Join us here before this offer ends.

Number 3: France — The Forced Upgrade Nightmare

Remember Mr. Graham from the introduction? The man from Phoenix whose savings were wiped out? His story happened in France. He bought what he thought was his dream apartment in a classic Bordelais building, only to receive an official letter mandating a ruinously expensive energy upgrade.

This is not a rare occurrence. This is French policy.

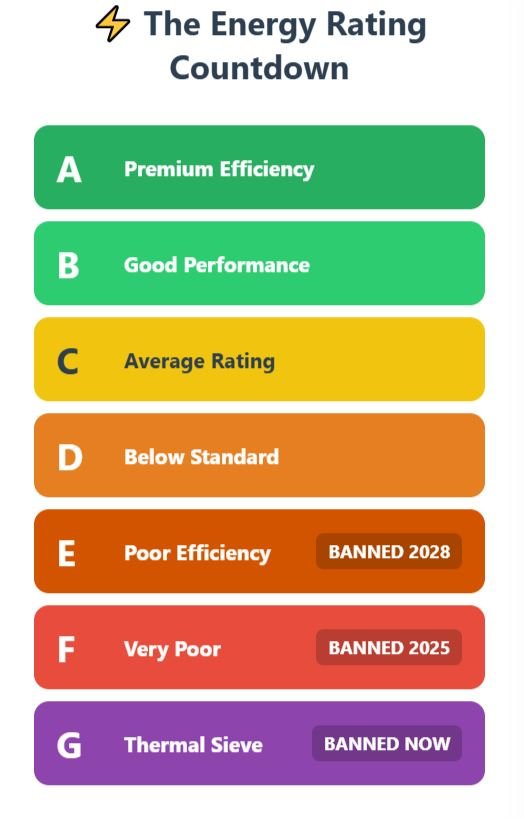

The reality is a program targeting ‘passoires thermiques’, which translates to ‘thermal sieves’. Every property receives an energy performance rating, the DPE, on a scale from ‘A’ to ‘G’. France is actively banning energy-inefficient homes from the rental market on a strict, legally-binding schedule. As of right now, if your property is rated ‘G’ or ‘F’, you are already forbidden from signing a new rental contract.

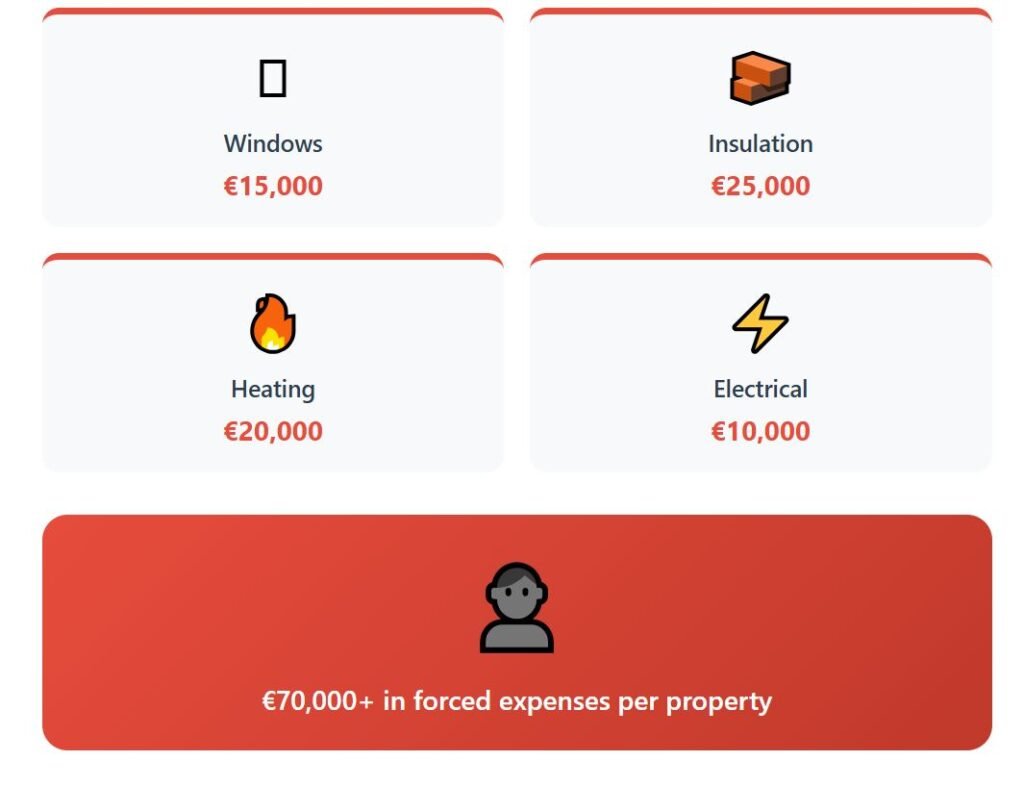

The ban extends to all ‘E’ rated homes in 2028. This covers a vast portion of the housing stock, especially the older, character-filled apartments that attract foreign buyers. The law forces you, the owner, to spend tens of thousands of euros on new insulation, windows, and heating systems. It’s a forced expense, mandated by the government, just for you to legally keep your property on the rental market.

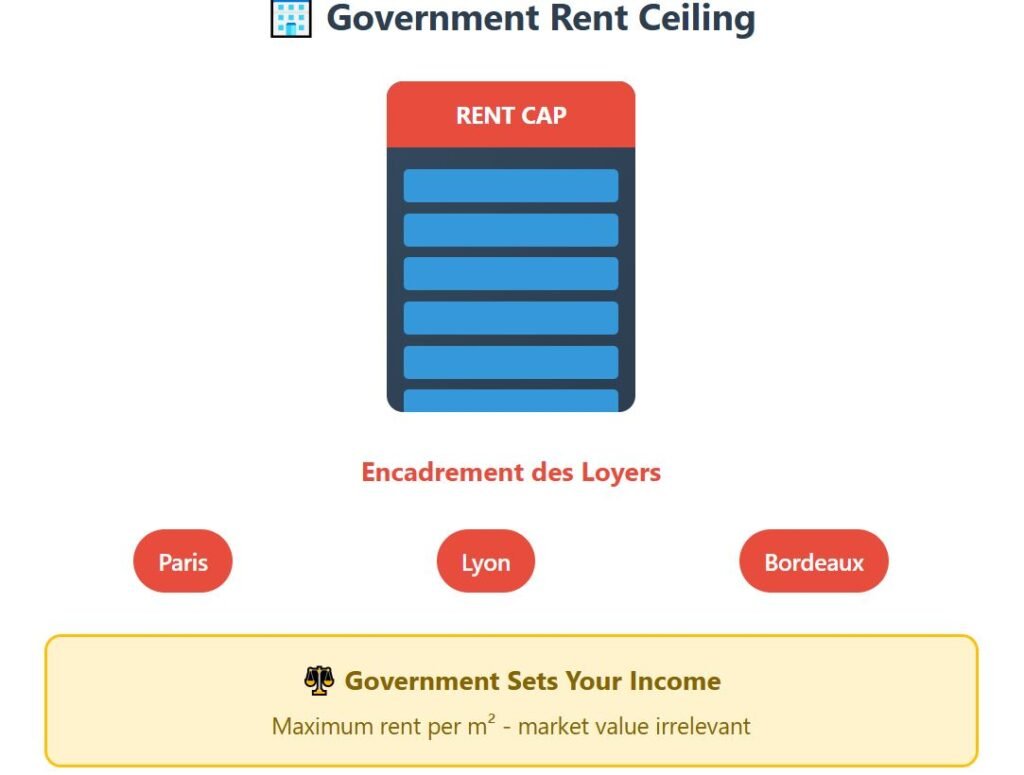

While the government forces you to spend money, it also limits how much you can make. In Paris, Lyon, Bordeaux, and a growing list of other cities, you face rent controls, known as ‘Encadrement des loyers’. This system sets a maximum rent per square meter that you are allowed to charge, and it doesn’t matter if you have a premium, fully renovated apartment in a prime location – the government, not the market, dictates your maximum income.

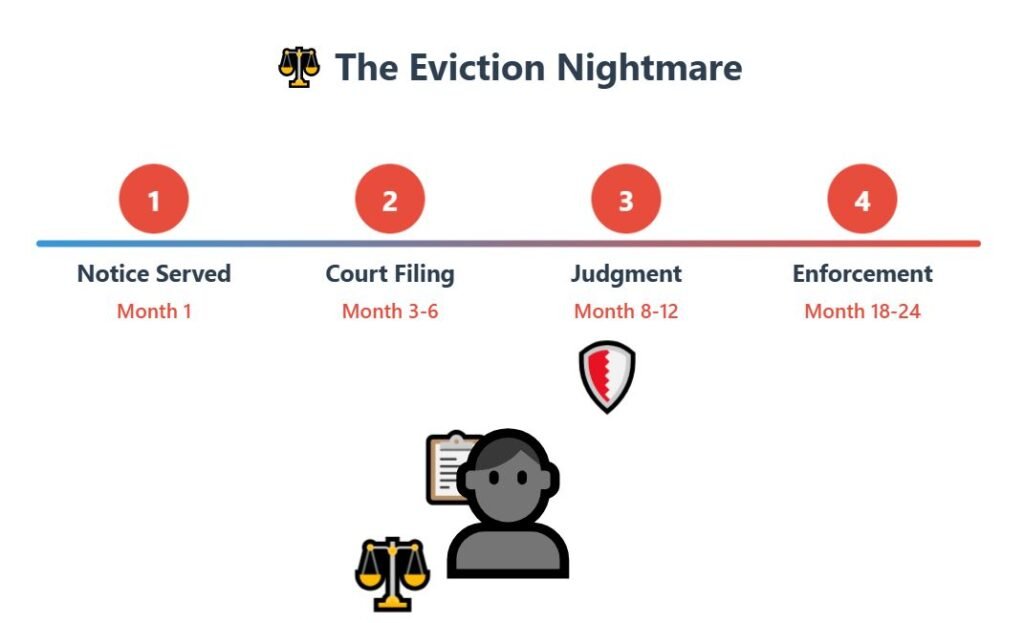

Then you have one of the most pro-tenant legal systems in Europe, and the eviction process is famously slow and expensive for landlords. If you have a tenant who stops paying rent, it can take years and thousands in legal fees to get your property back. And that’s not all – there is an annual period called the ‘trêve hivernale’, or the winter truce, which runs from November 1st to March 31st. During these five months, almost all evictions are legally forbidden, regardless of whether the tenant is paying.

Even getting into the market is costly: transaction costs on older properties are some of the highest in Europe. The buyer pays the notary fees, or ‘frais de notaire’, which typically amount to 7-8% of the purchase price. For a 500,000 property, that is up to 40,000 lost. If you don’t speak French, there are massive translation costs but then, this is not fault of the country. In my opinion, anyone planning to buy a second-house in a certain country should do their best to learn the language of that country.

And if you buy an expensive or large property, France penalizes you with the IFI, the ‘Impôt sur la Fortune Immobilière’ – a wealth tax that specifically targets real estate. If your properties exceed 800,000, you pay this punitive annual tax on top of all your other taxes.

Number 2: Austria — Stable, Safe, But With Financial Burdens

Austria offers an incredible quality of life, safety, and stability. But for a property investor, this stability comes at a steep price, because the entire system is engineered to protect tenants (both the good and the bad ones) at the direct expense of the landlord.

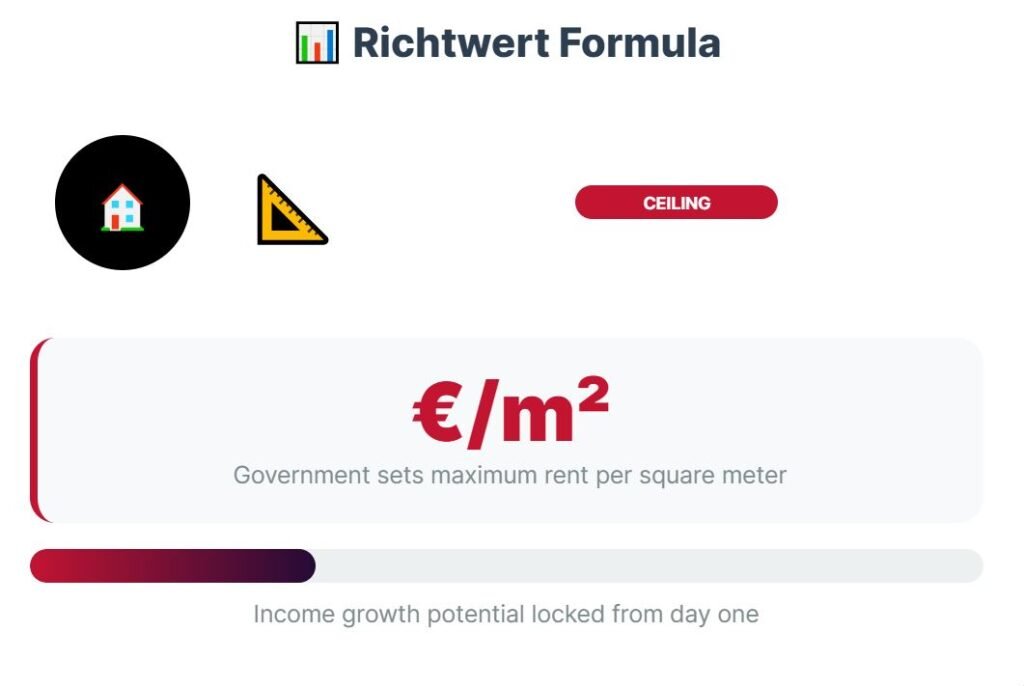

Many properties fall under a system of strictly regulated rents, known as ‘Richtwertmiete’. The government, through a formula, sets the maximum rent you can charge.

From the moment you buy the property, your potential for income growth is minimal by design, locking you into a low-yield environment from the start. This income cap is combined with some of the strongest tenant protection laws in Europe. If you have a problematic tenant who stops paying rent, the eviction process can become a legal battle lasting for years. During this entire period, you can expect to receive no rental income while continuing to pay the mortgage, taxes, and mounting legal fees.

You take on all the financial risk of ownership, while the potential for profit is legally capped, and the risk of a non-paying tenant is amplified by the system.

Then you face major barriers just to enter the market. Many of Austria’s provinces have strict ‘Zweitwohnsitz’ regulations – laws designed to prevent towns from being filled with unused vacation homes. For a non-resident, these laws can severely restrict or outright prohibit you from purchasing second homes.

On top of these restrictions, the transaction costs are high. You will pay a 3.5% real estate transfer tax on the purchase price. When you add notary fees, registration fees, and agent commissions, your total upfront cost can approach 10% of the property’s value.

Number 1: Switzerland — The Country That Just Says ‘No’

We’ve seen rent caps, forced upgrades, and policy chaos. But the worst country for a foreigner to buy property in Europe does something much simpler and far more absolute. It just says ‘no’. This is not an exaggeration.

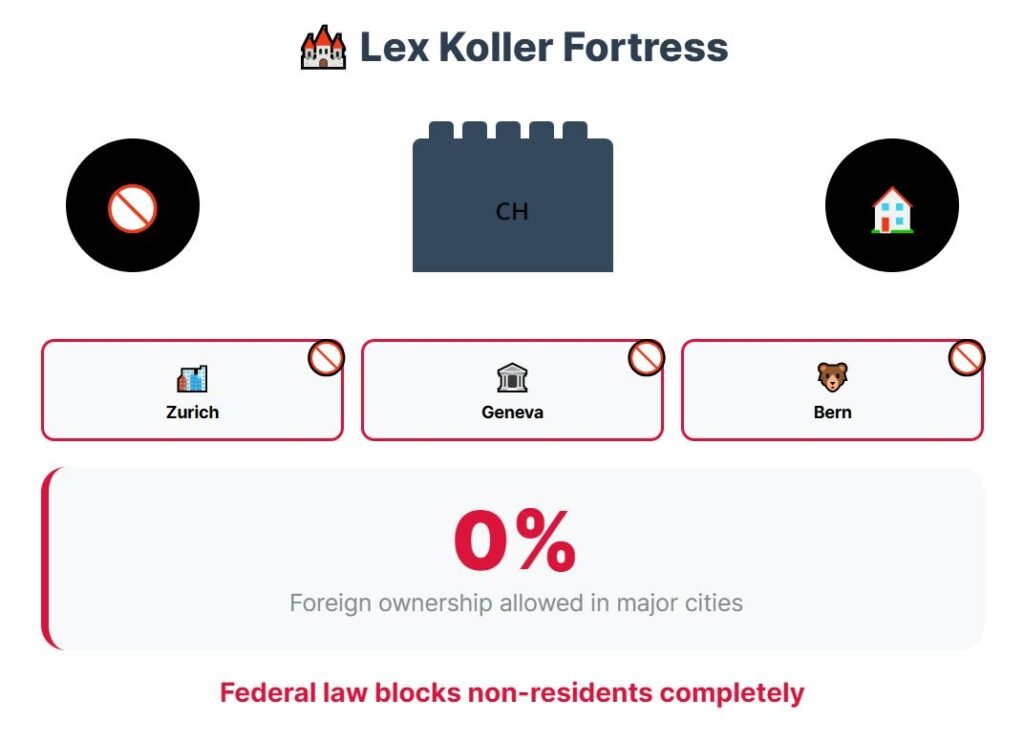

In Switzerland, a law known as ‘Lex Koller’ explicitly prohibits non-residents from purchasing residential property in most of the country unless they obtain a very complicated permit. For the purpose of this law, a non-resident is anyone who is not a Swiss national or does not hold a specific Swiss residence permit, typically a C-permit. This means that for the vast majority of foreign buyers, the conversation ends before it even begins.

The Lex Koller law technically is valid to all of Switzerland, but the enforcement and specific permits are managed by the individual cantons. Some cantons have more investor-friendly policies, while others, like Geneva and Vaud, have stricter regulations.

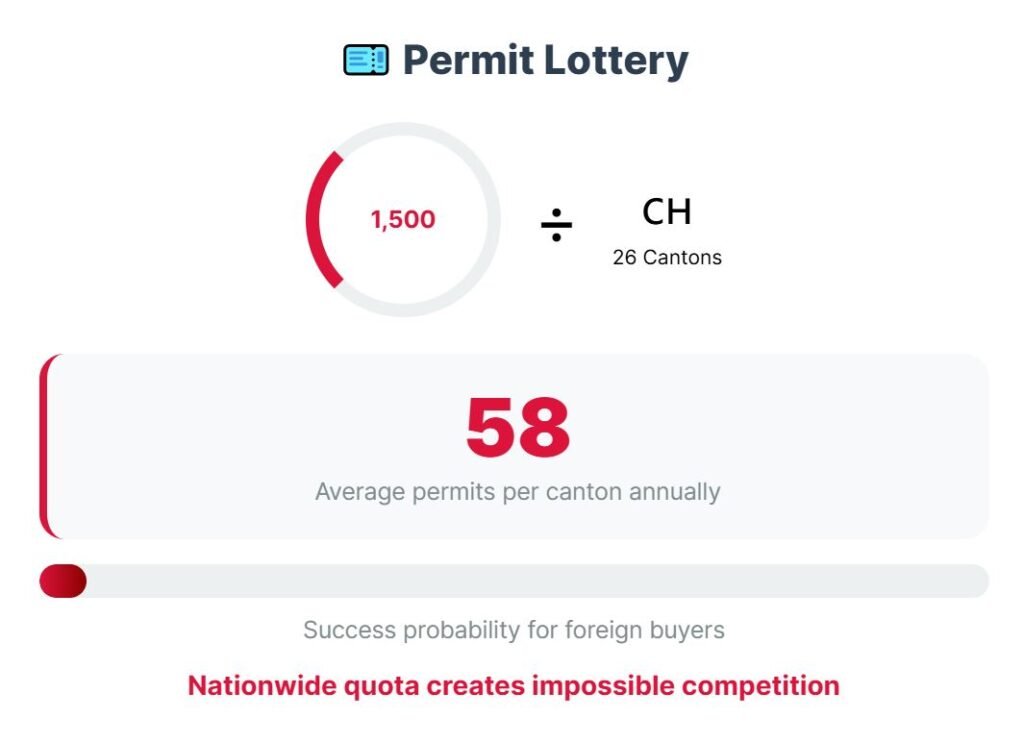

These zones are subject to a tiny national quota of permits, which is distributed among the cantons. For example, the annual quota to holiday homes is just 1,500 permits – for the entire country, and securing one is incredibly difficult and competitive. But even for the handful of people who might qualify for one of these rare permits, the hostility does not stop.

Another federal law, the ‘Lex Weber’ initiative, adds another brick to the wall. This law caps the number of second homes at 20% in any given commune, or municipality. Many of the desirable areas already hit this cap, so permits are no longer issued there. If you somehow navigate this legal minefield and manage to buy a property, there are also another huge obstacle.

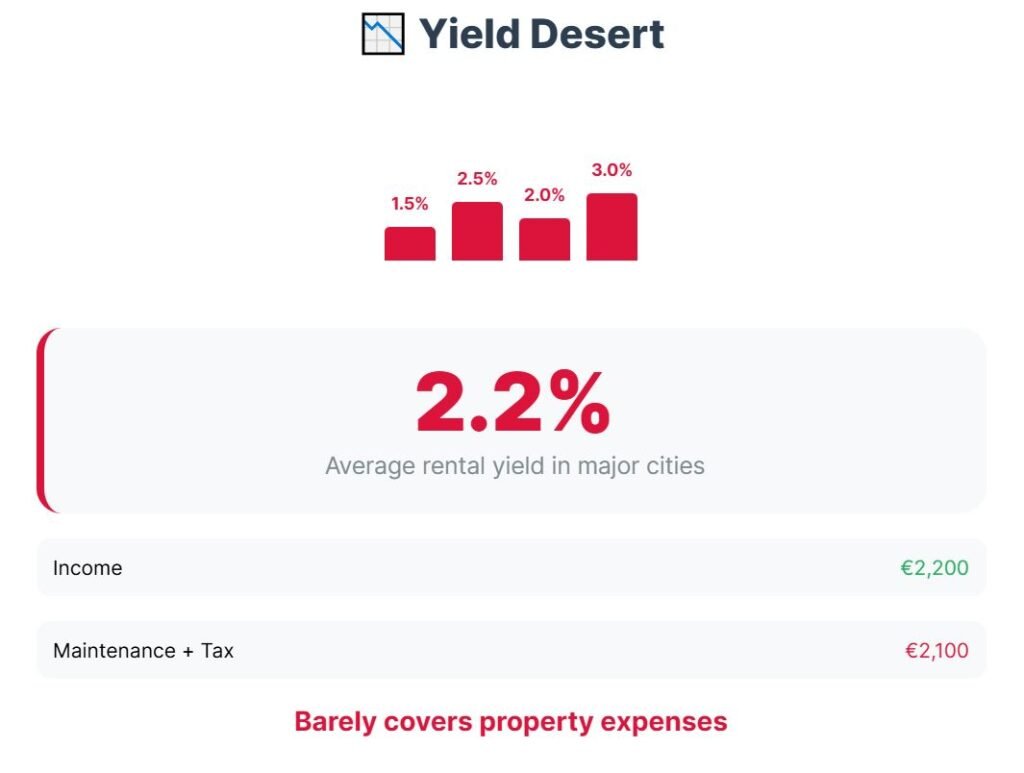

Swiss rental yields are the lowest in Europe, often falling between 1.5% and 3.0% in major cities. Your property will barely generate enough income to cover its own maintenance and taxes, let alone provide a return. Then you face a series of punitive taxes. The most notorious of these is the ‘Eigenmietwert’, or imputed rental value tax. This is a tax on the theoretical rent you could be collecting from your property, even if you are living in it yourself. You pay income tax on this phantom income.

Switzerland is not a real estate market for outsiders. It is a fortress designed to preserve the wealth of those already inside and legally keep everyone else out.

But not every place in Europe is like that – there are countries where you can buy a nice home for less than US$100,000 and with lower risks!

Levi Borba is the founder of expatriateconsultancy.com, creator of the channel The Expat, and best-selling author. You can find him on X here. Some of the links above might be affiliated links, meaning the author earns a small commission if you make a purchase.